Not Made in the USA: Our Global Pharmaceutical Supply Chain

Excerpt of and originally published as Section 3 in "Not Made in the USA: The Global Pharmaceutical Supply Chain and Prospects for Safe Drug Importation"

-

Section 3: Our Global Pharmaceutical Supply Chain

3.1. Data Overview of Pharmaceutical Imports

The finding in this report, that 78% of APIs for the dataset of 100 drugs are imported, appears to corroborate the FDA’s ubiquitous datapoint of 80%, but this dataset consists only of brand name drugs. It is likely that an even higher percentage of generic drugs are imported. Public Citizen’s Trade Watch data for 2019, on the volume and dollar values of the top 10 countries exporting pharmaceuticals to the U.S., supports that assertion.[i] The largest quantity of pharmaceutical imports is generic drugs and not from the most strongly regulated pharmaceutical markets. Notice that the top three countries for volume of pharmaceutical imports are 1) China, 2) India and 3) Mexico.

Top 10 U.S. Sources of Pharmaceutical Imports by Volume vs. Value of Those Imports (2019) |

||||

| Percent of Total | ||||

| Country | Kilograms | Dollar Value | Kilograms | Dollar Value |

| China | 101,950,825 | $1,614,171,438 | 22.46% | 2.05% |

| India | 97,847,782 | $7,597,811,241 | 21.56% | 9.65% |

| Mexico | 85,409,777 | $567,164,001 | 18.82% | 0.72% |

| Canada | 50,908,177 | $5,307,652,313 | 11.22% | 6.74% |

| Germany | 32,067,235 | $17,316,667,285 | 7.07% | 22.00% |

| Italy | 30,181,545 | $7,718,831,907 | 6.65% | 9.81% |

| United Kingdom | 16,736,681 | $5,101,369,001 | 3.69% | 6.48% |

| Israel | 13,529,322 | $2,209,704,960 | 2.98% | 2.81% |

| Spain | 12,680,293 | $1,323,775,643 | 2.79% | 1.68% |

| Ireland | 12,522,083 | $29,941,109,004 | 2.76% | 38.05% |

| Total | 453,833,720 | $78,698,256,793 | ||

Source: Public Citizen, 2019

In our dataset of 100, China and India each accounted for only one API.

After the top three countries for pharmaceutical imports, the rest are high-income countries: 4) Canada, 5) Germany, 6) Italy, 7) the United Kingdom, 8) Israel, 9) Spain, 10) Ireland. In looking at the dollar value data, the bulk of imports from high-income countries must be brand name APIs and FDFs. Ireland, for example, makes up only 2.76% of the volume of the top 10, but a plurality, 38.05%, of the dollar value. That reflects the much higher cost of brand name vs. generic drugs. The inverse is true of China: its import volume is 22.46% of the top 10 countries, compared to only 2.05% of the dollar value. This data confirms that high-income countries with the strongest pharmaceutical regulations are mostly responsible for the manufacture of our brand name drugs. Further validating evidence is found in a survey conducted in 2018 showing biopharma industry perceptions of countries that lead in the manufacture of biologics in which the top countries identified are the U.S., Germany, Japan, Italy, the UK, and Ireland.[ii]

Two salient truths that contradict the prevailing communications narrative of the FDA in both instances, and biopharmaceutical industry in just the latter, are identified and explained in this section of the paper:

- One, brand name drugs are likely to be of higher quality than generics. That is because branded finished products and their active pharmaceutical ingredient are mostly made in countries with the strongest regulations for pharmaceutical manufacturing.

- Two, as a corollary of the above, there is no reason to prevent importing of lower cost brand name drugs into the U.S. based on arguments over risks of lower drug quality.

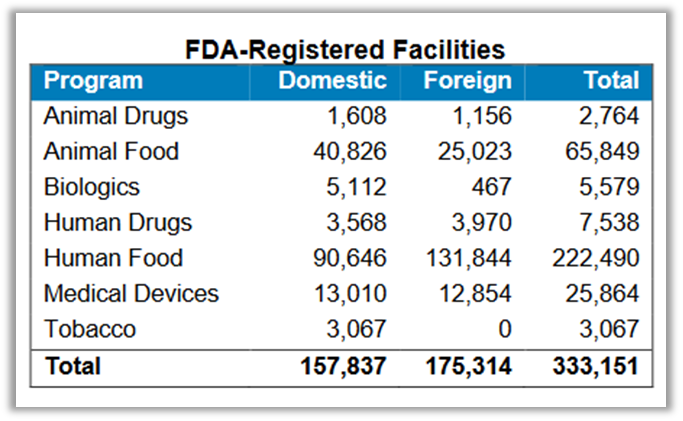

3.2. FDA Registration and Recordkeeping About Foreign Made Drugs: APIs and FDFs

Source: FDA, 2019

This section explores the FDA’s statutory mandate for registering and recordkeeping of drug imports, clarifies what data they do and do not have, and what we should expect from the agency. As stated above, the GAO, relying on FDA data, asserted in 1998[iii] and as recently as 2019, that 80% of APIs in U.S. drugs are foreign made.[iv] The fact that this figure remained unchanged after 20 years would have us conclude that the globalization of pharmaceutical manufacturing happened long ago and is not necessarily increasing at all. It also indicates lack of FDA’s data accuracy and highlights the GAO’s failure to question that data.

In 2019, the FDA stated that not only does it not know the exact percentage of APIs that are imported but it cannot know.[v] In Congressional testimony for a hearing called “Safeguarding Pharmaceutical Supply Chains in a Global Economy,” in October of 2019, then FDA Director of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER), current acting FDA Commissioner Janet Woodcock, MD, stated:

although CDER can describe the locations of API manufacturing facilities, we cannot determine with any precision the volume of API that China is actually producing, or the volume of APIs manufactured in China that is entering the U.S. market, either directly or indirectly by incorporation into finished dosages manufactured in China or other parts of the world.”

data available to FDA do not enable us to calculate the volume of APIs being used for U.S.-marketed drugs from China or India, and what percentage of U.S. drug consumption this represents.”

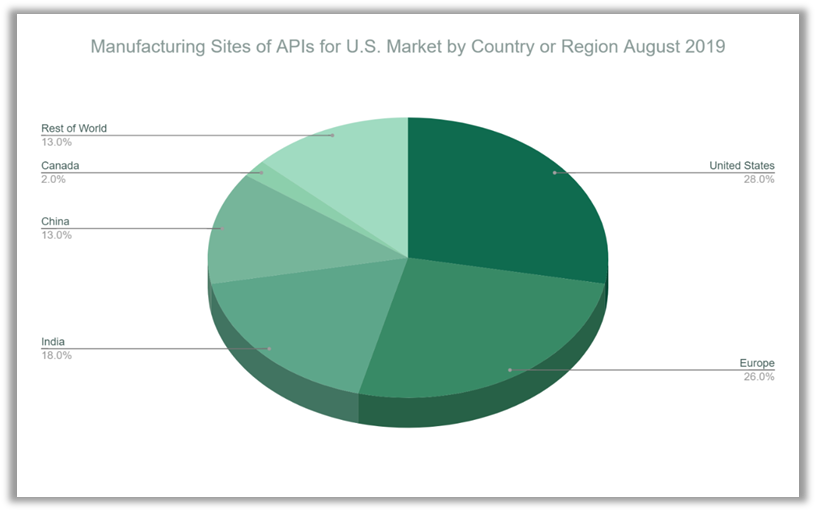

This registration data is helpful in assessing dependency on foreign drug supplies and as an overview of what countries and regions are key sources of APIs for the United States. FDA’s data does show a growing number of Chinese API producers registered with the FDA but also very strong European penetration in this market. FDA’s data also shows that 72% of registered facilities are based outside the United States, which closely corroborates the pharmaceuticals import data in “Not Made in the USA.”

With a total of 1,788 registered manufacturing establishments, the largest share after the U.S. is in Europe: 456 facilities. This data approximates the findings in “Not Made in the USA” and Public Citizen’s analysis of U.S. trade data that both show a very prominent role played by European countries in supplying the U.S. with brand name drugs.

The statutory registration requirements for drug manufacturers under federal law do not require the FDA to track the volume of pharmaceutical imports but do require that the FDA keep records at the national drug code (NDC) level of where finished drugs and APIs are made:

Every person who registers with the Secretary under subsection (b), (c), (d), or (i) shall, at the time of registration under any such subsection, file with the Secretary a list of all drugs and a list of all devices...which are being manufactured, prepared, propagated, compounded, or processed by him for commercial distribution and which he has not included in any list of drugs or devices filed by him with the Secretary under this paragraph or paragraph (2) before such time of registration. Such list shall be prepared in such form and manner as the Secretary may prescribe and shall be accompanied by-”

For foreign establishments specifically:

1) Every person who owns or operates any establishment within any foreign country engaged in the manufacture, preparation, propagation, compounding, or processing of a drug or device that is imported or offered for import into the United States shall, through electronic means in accordance with the criteria of the Secretary- (A) upon first engaging in any such activity, immediately submit a registration to the Secretary that includes-…the name and place of business of such person, all such establishments, the unique facility identifier of each such establishment..."

Source: FDA, 2020

Based on those requirements, a database should exist in which the FDA can immediately refer to the name and location of the manufacturer for any given API or FDF. Drug manufacturers often work with several companies to supply them with the same API, which could possibly complicate mandated recordkeeping, but for FDFs it is more straightforward. Each FDF has an NDC number, which is associated with a drug application that must have the name and location of the manufacturer. Based on those requirements, the FDA drug database should be able to provide accurate information on the percentage of available drugs — but not the volume — that are imported, at least under the FDA’s definition (contrasted with the definition of the CBP). If any such report or recordkeeping exists, it is not referenced by the FDA as the basis for its claims about the percentage of the U.S. drug supply that is imported.

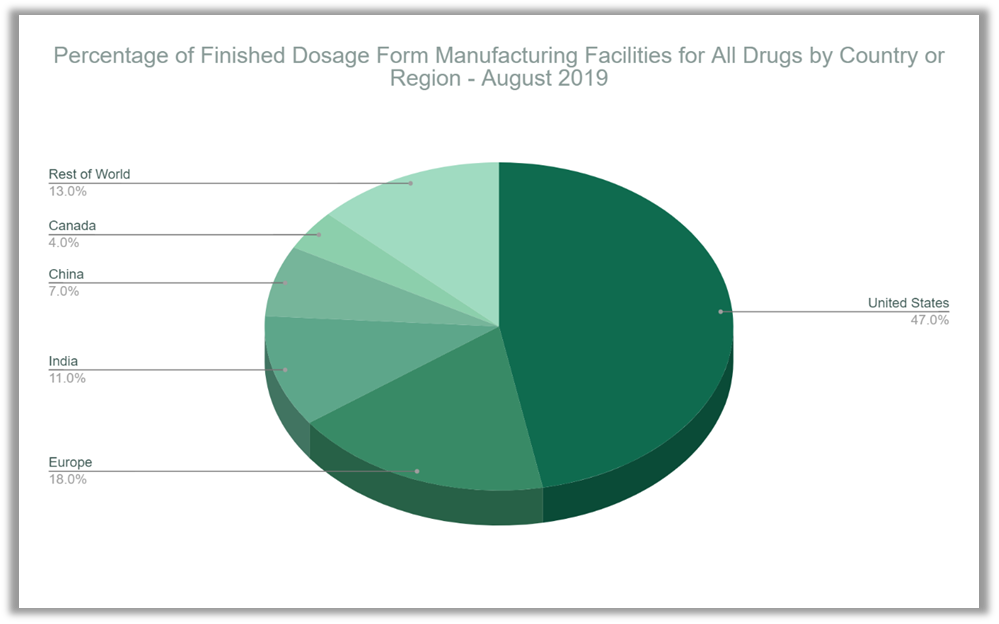

Where the FDA falls short on recordkeeping or transparency about imported drugs, it has improved its procedures for registering and updating drug establishments that manufacture drugs for the U.S. market, a product of the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Improvement Act of 2012. An FDA Fact Sheet from November 2020 shows that there are a total of 7,538 registered human drug establishments, many of which do not actually produce drugs but re-package and re-label them.[x] It states that “(a)bout 80 percent of active pharmaceutical ingredient manufacturers are located outside of the U.S.” Notice that the statistic is about foreign API manufacturers, not API import volumes or products. In other testimony before Congress, in December 2019, Dr. Woodcock submitted a breakdown of establishments registered with the FDA for making FDFs, which contain a surprisingly high percentage — 47% — located in the United States.[xi]

Source: FDA, 2019

That figure does not square with the percentage of FDFs sold in the U.S. that are produced domestically. The reason is that many such establishments are labelers and packagers — not manufacturers.

3.3. Brand vs. Generic Drug Supply Quality Concerns

3.3.1. Foreign Generic Drug Manufacturing Quality

The public perception is that there are more quality problems with generic drugs than brand name drugs.[xii] Drug testing demonstrates that this perception is based on the reality that a significant number of generic drugs are not interchangeable with their brand name counterparts or with other generic counterparts (different manufacturers of the same drug) due to quality problems.[xiii] [xiv] This is not a reason to fearmonger about or discourage use of generic drugs. Most generic drugs in the U.S., in high-income countries generally, and those of the top manufacturers in India as well, are generally of high quality and are the foundation for drug accessibility and affordability in the U.S. and globally.[xv] [xvi] [xvii]However, ignoring the fact that generic drugs are more likely to have quality control problems and that brand name drugs are generally made in countries with the strongest pharmaceutical regulations will hinder our ability to make the best public health and healthcare financing decisions.

Over the past two decades, periodic GAO reports have criticized the FDA for not adequately inspecting foreign drug manufacturing establishments that export pharmaceuticals to the United States.[xviii] [xix] [xx] [xxi] Subpar inspections of API manufacturing facilities, located in countries with weaker pharmaceutical regulations, are usually discussed as a growing problem that is overwhelmingly associated with India and China, the world’s largest producers of pharmaceutical ingredients. As recently as March 2021, the GAO released a report documenting a lack of confidence in FDA inspection activities during the COVID-19 pandemic:

We have long-standing concerns about the Food and Drug Administration's ability to oversee the increasingly global pharmaceutical supply chain.”[xxii]

The ubiquitous criticism of the agency notwithstanding, the FDA, as noted above, has improved its protocols for inspecting and registering foreign drug establishments, but its ability to inspect was hampered by the pandemic.

India is a longtime, major supplier of generic drugs, FDFs and APIs, to the United States. A Chemistry and Engineering News article summarizes the trend of U.S.-sold generics imported from India:

In 1990, about 50% of ANDAs [abbreviated new drug applications (generics)] came from U.S. firms and 15%, from India. By 2012, U.S. company filings had dropped to 30% and Indian ones had grown to 40%.”[xxiii]

In a CNBC article from March 24, 2020, Rohit Bhat, research analyst at B&K Securities, estimated that India accounts for 40-50% of all generic drugs.[xxiv] Also, according to that article, India imports 70% of its APIs from China for its own drug supply. It is not documented how many of those APIs are used to manufacture FDA-approved drugs formulated in India; this is an opaque aspect of the supply chain where tallying Chinese-made APIs in U.S. drugs is difficult.[xxv]

Drug manufacturing problems and regulatory non-compliance happen in the U.S. and in other high-income countries, but not to the degree found in India and China.[xxvi] Both India and China have state-of-the-art pharmaceutical manufacturing capacities that produce drugs of the highest quality — but also many lower-quality producers.[xxvii] “Bottle of Lies: The Inside Story of the Generic Drug Boom,” by investigative journalist Katherine Eban, uncovered numerous cases of corruption and incompetence by drug manufacturers in India. The book presents a scathing view of the FDA, accusing the agency of turning a blind eye to this corruption and alleging that the “generic drug boom” of the past two decades has gone hand in hand with poor regulatory oversight.[xxviii] The authors of “Not Made in the USA” hold a less critical perspective, but Ms. Eban’s important reporting corroborates the position taken here that brand name drugs are sometimes of higher quality than generics: because they are far more likely to be produced in countries with the strongest pharmaceutical regulations.

3.3.2. Regulatory Equivalence Or Superiority in Other High-Income Countries

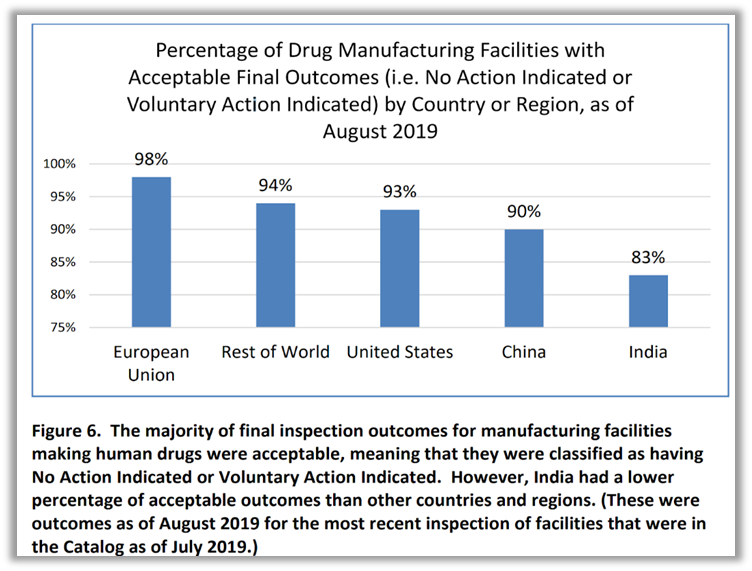

“Not Made in the USA” data shows that brand name drugs are mostly made outside the U.S. in high-income countries with strong regulatory standards and oversight bodies. The FDA officially recognizes the strong pharmaceutical regulations of these trading partners. As of 2019, the FDA had entered into mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) with all 28 (now 27) member countries of the European Union that allow the FDA to recognize the results of foreign drug manufacturing facility inspections for Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs) by one of the MRA countries.[xxix] [1]

The FDA's decision to rely on the regulators of other countries is supported by research conducted by the agency’s leadership showing the superiority of foreign regulators, particularly those in the EU. That research led the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to see the benefits of personal drug importation for patients to save money. In a question-and-answer page offered on the HHS website, it stated, “Can individuals trust that imported prescription drugs are safe?”[xxx]:

Source: FDA, 2019

A recent report based on the largest ever comparative test of the quality attributes of prescription drugs legally marketed in the United States concluded that ‘difficult-to-make prescription pharmaceuticals marketed in the US consistently meet quality standards even when manufactured outside the US.’”[xxxi]

The report found that manufacturing facilities in the EU had the strongest outcomes for compliance, noticeably superior to U.S.-based facilities. While drug manufacturing facilities in the U.S. had better outcomes than those in China and India, they were slightly worse than other countries generally. [xxxii] Furthermore, quality testing results for brand name drugs were notably stronger than those for generic drugs. The report stated, “all drugs met the tested standards, brand-name drugs generally had higher process performance for dissolution [than generic drugs].”[xxxiii]

It bears repeating that the greater degree of quality control with brand name drugs is not to diminish the importance and necessity of generic drugs for managing the cost of and access to pharmaceuticals. Properly manufactured generics, meaning those made with high quality ingredients and under GMP, work just as well as their brand name counterparts. Valisure, an online pharmacy and independent drug testing laboratory in the U.S., finds that 90% of generic drugs they test meet quality standards.[xxxiv] Those tests surpass the FDA’s protocols for ensuring drug quality.[xxxv] In an overwhelming majority of cases, FDA-approved generics work just as well as the brand. The problem is that a 10% failure rate is too high.

3.3.3. National Security

As regulators and policymakers continue to examine potential vulnerabilities of the U.S. pharmaceutical supply, concerns are often placed on imports from China and, to a different degree, India. In view of the global coronavirus pandemic, quality and accessibility of pharmaceuticals are viewed with greater urgency.[xxxvi] In March 2021, President Biden issued an executive order requiring review of critical supply chains with a stated aim to boost domestic manufacturing of pharmaceuticals.[xxxvii]

In the case of China, pharmaceutical supply chains are a source of vulnerability, the degree to which is an important topic for policymakers. However, “Not Made in the USA” shows that such vulnerabilities may not apply to the manufacture of brand name drugs. While China is the largest supplier of pharmaceutical ingredients to the U.S., only one drug in our sample of 100 drugs was made with an API from China.

The FDA has identified APIs and pharmaceuticals that demonstrate the level of U.S. dependence on China.[xxxviii] To counter those vulnerabilities, public policies that develop and ensure adequate domestic or alternative global pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity are necessary. Thus, in addition to building more domestic manufacturing capacity, the FDA’s data and this report show alternative global manufacturing bases beyond China, notably in the EU and India, that can be tapped in emergencies.

Exaggerations about the U.S. drug supply’s vulnerability can lead to bad policy and public health consequences, due to a lack of trust in the efficacy of prescription drugs and even higher drug prices that would result from more protectionist trade policies. To protect and improve drug safety, getting the data right is critical before embarking on dramatic regulatory reforms. Reasonable efforts to build more domestic manufacturing capacity need not trample on a more efficient and safer global marketplace for pharmaceuticals.

[1] Furthermore, the European Union, which has led global regulatory cooperation on pharmaceutical manufacturing, also has MRAs with Australia, Canada, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, and Switzerland. See: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/compliance/good-manufacturing-practice/mutual-recognition-agreements-mra#canada-section.

[i] China is the top source of U.S. Pharmaceutical imports, with India and Mexico also major sources. (2020, April 7). Public Citizen. https://www.citizen.org/article/china-is-the-top-source-of-us-pharmaceutical-imports/

[ii] Rais, A. (2018, August 31). USA, Germany and Japan are top 3 bio manufacturing countries. Process Worldwide. https://www.process-worldwide.com/usa-germany-and-japan-are-top-3-bio-manufacturing-countries-a-749329/

[iii] GAO, supra note 3.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Safeguarding pharmaceutical supply chains in a global economy. (2019, October 29). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/congressional-testimony/safeguarding-pharmaceutical-supply-chains-global-economy-10302019

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] 21 USC §360. Registration of producers of drugs or devices. (2021). Title 21-FOOD AND DRUGSCHAPTER 9-FEDERAL FOOD, DRUG, AND COSMETIC ACTSUBCHAPTER V-DRUGS AND DEVICES Part A-Drugs and Devices. https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=(title:21%20section:360%20edition:prelim)

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Drug safety: FDA has improved its foreign drug inspection program, but needs to assess the effectiveness and staffing of its foreign offices. (2016, December). U.S. Government Accountability Office (U.S. GAO). https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-17-143

[x] FDA at a glance: regulated products and facilities. (2020, November). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/media/143704/download

[xi] Woodcock, J. (2019). Securing the U.S. drug supply chain: Oversight of FDA's foreign inspection program. In Hearing before the subcommittee on oversight and investigations of the committee on energy and commerce, House of Representatives, one hundred sixteenth Congress, first session, December 10, 2019. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. https://docs.house.gov/meetings/IF/IF02/20191210/110317/HHRG-116-IF02-Wstate-WoodcockMDM-20191210.pdf

[xii] Dunne, S. S., & Dunne, C. P. (2015). What do people really think of generic medicines? A systematic review and critical appraisal of literature on stakeholder perceptions of generic drugs. BMC Medicine, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0415-3

[xiii] Team Valisure. (2020, September 9). All generics are not created equal. Valisure. https://www.valisure.com/blog/valisure-notebook/all-generics-are-not-created-equal/

[xiv] Fisher, A. C., Viehmann, A., Ashtiani, M., Friedman, R. L., Buhse, L., Kopcha, M., & Woodcock, J. (2020). Quality testing of difficult-to-make prescription pharmaceutical products marketed in the US. JAMA Network Open, 3(8), e2013920. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13920

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Light, D. (2020). COVID-19 and beyond: oversight of the FDA’s foreign drug manufacturing inspection process. Hearing before the United States Senate Committee on Finance June 2, 2020 (Testimony of David Light, Founder and CEO, Valisure). https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/02JUN2020.VALISURE.LIGHT.STMNT.pdf

[xvii] Desai, R. J., Sarpatwari, A., Dejene, S., Khan, N. F., Lii, J., Rogers, J. R., Dutcher, S. K., Raofi, S., Bohn, J., Connolly, J. G., Fischer, M. A., Kesselheim, A. S., & Gagne, J. J. (2019). Comparative effectiveness of generic and brand-name medication use: A database study of US health insurance claims. PLOS Medicine, 16(3), e1002763. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002763

[xviii] Food and Drug Administration: Improvements needed in the foreign drug inspection program: Report to the chairman, subcommittee on oversight and investigations, committee on commerce, House of Representatives. (1998). United States General Accounting Office. https://www.gao.gov/assets/hehs-98-21.pdf2007: https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-08-224t

[xix] Drug safety: FDA has conducted more foreign inspections and begun to improve its information on foreign establishments, but more progress is needed : report to the committee on oversight and government reform, House of Representatives. (2010). United States Government Accountability Office. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-10-961

[xx] Drug safety: FDA has improved its foreign drug inspection program, but needs to assess the effectiveness and staffing of its foreign offices. (2017). United States Government Accountability Office. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-17-143

[xxi] Drug safety: Preliminary findings indicate persistent challenges with FDA foreign inspections (Statement of Mary Denigan-Macauley). (2019). United States Government Accountability Office. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-20-262t

[xxii] Drug safety: FDA's future inspection plans need to address issues presented by COVID-19 backlog: Testimony before the subcommittee on agriculture, rural development, Food and Drug Administration, and related agencies, committee on appropriations, House of Representatives (Statement of Mary Denigan-Macauley). (2021). United States Government Accountability Office. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-409t

[xxiii] Thayer, A. M. (2014). 30 years of generics. Chemical & Engineering News Archive, 92(39), 8-16. https://doi.org/10.1021/cen-09239-cover

[xxiv] Fears of US drug shortages grow as India locks down to curb the coronavirus. (2020, March 24). CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/24/us-drug-shortage-fears-grow-as-india-locks-down-due-to-the-coronavirus.html

[xxv] Huang, Y. (2019, August 14). U.S. dependence on pharmaceutical products from China. Council on Foreign Relations. https://www.cfr.org/blog/us-dependence-pharmaceutical-products-china

[xxvi] Bate, R. (2012). Phake: The deadly world of falsified and substandard medicines. Rowman & Littlefield.

[xxvii] Ibid.

[xxviii] Eban, K. (2019). Bottle of lies: The inside story of the generic drug boom. HarperCollins.

[xxix] Mutual recognition agreement (MRA). (2020, May 8). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/international-programs/international-arrangements/mutual-recognition-agreement-mra

[xxx] Fulfilling president Trump’s executive order on facilitating drug importation to lower prices for American patients: request for industry proposals for personal importation of prescription drugs. (2020). United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/individual-prescription-drug-importation-faq.pdf

[xxxi] Ibid.

[xxxii] Fisher, supra note 54.

[xxxiii] Bate, supra note 66.

[xxxiv] Johnson, C. Y. (2019, November 8). A tiny pharmacy is identifying big problems with common drugs, including Zantac. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/science/a-tiny-pharmacy-is-identifying-big-problems-with-common-drugs-including-zantac/2019/11/08/6dd009ca-eb76-11e9-9c6d-436a0df4f31d_story.html

[xxxv] Light, supra note 56.

[xxxvi] Tankersley, J., & Swanson, A. (2021, February 24). Amid shortfalls, Biden signs executive order to bolster critical supply chains. The New York Times - Breaking News, US News, World News and Videos. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/24/business/biden-supply-chain-executive-order.html

[xxxviii] Safeguarding, supra note 45.