Importation as Policy to Lower Prescription Drug Prices

All things prescription drug importation and public policy can be found in Section 4 of Not Made in the USA. Want to know more about the laws and regulations? How about state drug importation laws, plans, and problems? Can I get a shout-out for my old-time favorite, personal drug importation? The political economy of the FDA’s cozy relationship with Big Pharma and how it shapes its anti-importation agenda? Read on for all of the above and more.

Below is an excerpt of and originally published as Section 4 in "Not Made in the USA: The Global Pharmaceutical Supply Chain and Prospects for Safe Drug Importation."

-

Section 4. Importation as Policy to Lower Prescription Drug Prices

The U.S. drug supply chain relies on pharmaceuticals produced in other countries and drugs are priced much lower in those foreign countries. For years, federal law has unnecessarily protected drug companies by preventing commercial or wholesale pharmaceutical trading that would lower drug prices here. Recent developments have opened the door to end that protectionism. Policymakers and businesses interested in drug importation can make use of “Not Made in the USA” data to identify products for wholesale or personal importation permissible under current law. Legislative reforms, however, are still necessary to use importation to more substantially lower drug prices for Americans.

The pharmaceutical and the U.S. pharmacy industries oppose new drug importation pathways as a means to make lower drug prices available to Americans.[i] [ii] Those industries would generate lower profits if public policies encouraged and led to substantially greater drug importation.[iii] The industry’s public opposition focuses on the potential for importing lower quality or counterfeit drugs from countries with weak regulations[iv] and funding organizations to exaggerate the threats.[v] [vi] [vii] [viii] [ix] [x] “Not Made in the USA” shows the hollowness of the industry’s opposition, especially when it comes to importing lower-priced brand name prescription drugs from high-income countries.

Section 4 explores four drug importation pathways to lower drug prices in the United States. The fifth and final subsection lists practical policy recommendations for the federal government given the findings in “Not Made in the USA.”

4.1. Wholesale (“Commercial”) Drug Importation

4.1.1. History and Limitations of Current Law

In 2000, the Medicines Equity and Drug Safety Act (the “MEDS Act”) created Section 804 of the FDCA to allow, as a means to lower drug prices for American payers, wholesale drug importation from 25 countries: Australia, Canada, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, Switzerland, or South Africa; and countries of the European Union (18 member states at the time).[xi] The “poison pill” in the law was that, in order for it to come into effect, it was required that the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services certify that the proposed importation: (1) pose no additional risk to the public's health and safety; and (2) result in a significant reduction in the cost of covered products to the American consumer.[xii] Essentially, if those certifications had been made, Section 804 would have integrated the United States with the EU and other countries in a system of free trade in pharmaceuticals at the wholesale level with accompanying beneficial competitive price effects: lower drug prices in America.

In 2003, the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act amended Section 804 to only permit wholesale drug importation from Canada, but it added important and expansive provisions to allow personal drug importation based on “enforcement discretion,” waivers, or regulatory guidelines.[xiii] This revision contained the same certification requirements as the MEDS Act. However, as discussed below, it set a different, more permissive standard for personal drug importation.

The certification called for under Section 804 by the HHS Secretary is one upon which the FDA, an agency under HHS’s authority, would play a lead role. For two decades now, the FDA’s intransigence and pharmaceutical industry lobbying of the FDA, explains why, until 2020, no HHS Secretary made the certification.

The status quo on drug importation and Section 804 was upended under the Trump administration. An executive order was issued on Jul 24th, 2020, calling for certification and the finalizing of the rules to implement Section 804; waiver authorities, creating new permissions of personal drug importation; and reimportation of insulin pursuant to Section 801 of the FDCA.[xiv] Under the Trump administration, on September 23rd, 2020, the Section 804 certification was officially made by HHS Secretary Alex Azar.[xv] Thus, pursuant to Section 804 of the FDCA, and new federal implementing rules, it is legal for entities other than drug manufacturers to import and resell lower cost prescription drugs from Canada.[xvi] While the Biden Administration revoked other executive orders on drug prices issued under the Trump administration, the one supporting importation remains.

On November 23rd, 2020, the Pharmaceutical Researchers and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), the Partnership for Safe Medicines, and the Council for Affordable Health Coverage filed a lawsuit to overturn HHS’s Section 804 certification and the final rule.[xvii] The Biden administration, while signaling that wholesale importation from Canada under Section 804 may not happen soon, defended the certification and final rule of Section 804 in a motion to dismiss PhRMA’s lawsuit.[xviii]

4.1.2. State Importation Programs and Section 804

Section 804 makes wholesale importation of prescription drugs from Canada legal by entities other than the manufacturers of those drugs, subject to implementing protocols to ensure the safety of the process.[xix] Those protocols include mandated reporting on drugs intended for import, batch testing for quality, and registration of Canadian wholesale pharmacies.[xx] Before wholesale importation can commence under Section 804, Section 804 sponsors must present their programs to the HHS Secretary for approval under the new rule. Thus, administrative obstacles remain as it relates to new wholesale Canadian drug importation programs.[xxi]

With prescription drug costs becoming a larger share of state budgets, among other policies to tackle drug prices, several U.S. states have passed laws to encourage wholesale importation from Canada, subject to Section 804 rules. In 2017, the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP), as part of its project to help lower the cost of prescription drugs, published model state legislation for the importation of drugs from Canada.[1] [xxii] [xxiii] Six states have passed drug importation laws that to varying degrees rely on the NASHP model legislation. Under the final rule, to implement Section 804, states are required to submit to their importation program plans to HHS for approval before importing.[xxiv] Several states have submitted their Section 804 plans to HHS, but none are approved.

Importation from Canada under Section 804 may provide some prescription savings for states and their residents, but the programs have important limitations and face obstacles to advancement. Notably, the law excludes importation of biologics, the most expensive medical products and the ones that account for an increasing percentage of spending on pharmaceuticals.[xxv] [xxvi] It also excludes controlled drugs, such as prescription opioids, benzodiazepines, and amphetamine-based medicines, intravenous and inhaled drugs. [xxvii]

Moreover, the federal rule only allows drugs to be imported from Canadian wholesalers that received those drugs directly from manufacturers, a restriction not required under Section 804.[xxviii] This requirement will weaken the competitive benefits of importation by making it easy for drug manufacturers to limit supplies to those Canadian wholesalers that are exporting products to the United States. That concern is well founded because the pharmaceutical industry has a history of instituting supply restrictions on Canadian pharmacies that sell prescription drugs to U.S. consumers for personal import.[xxix] Large pharmaceutical companies have software to accurately predict the number of pharmaceuticals that an economically advanced country uses for its own population. They will not likely cooperate by increasing the number of drug supplies for Canadian wholesalers to export to the United States. This part of the new rule undermines the price competitive benefits of importation by helping pharmaceutical companies maintain their distribution monopolies.

As the U.S. has determined that the importation of prescription drugs approved for sale in Canada poses no additional risk to the public health, there is no need to create a distribution bottleneck that empowers drug manufacturers. Another reason it is unnecessary to require that imported drugs come from a Canadian wholesaler that received them directly from their manufacturers is that Section 804 requires independent batch testing, beyond the requirements mandated for importation by drug manufacturers. In effect, due to enhanced testing, the Section 804 drug imports have potentially greater safety profiles than other drugs sold in the United States.[xxx]

Perhaps the most difficult obstacle has become the Canadian government’s position that the new Section 804 importation pathway is a potential threat to maintaining adequate drug supplies for Canada (which has a population about 12% the size of the United States).[xxxi] Fearing potential shortages, Canada issued an interim order in response to Section 804 requiring Canadian wholesale pharmacies to demonstrate, prior to export, that exports will not create domestic shortages.[xxxii] Eligible wholesale pharmacies in Canada would need to increase their orders from manufacturers to meet U.S. demands, while not jeopardizing local Canadian supplies.

Overall, the Section 804 importation pathway from Canada has limited long-term impact because the Canadian market’s small size threatens to restrict the American supply.[xxxiii] However, the drawbacks mentioned are not insurmountable to achieve substantial savings on some patented and off-patent expensive non-biologic drugs. Some of the drugs mentioned in this report are candidates for savings.

In the longer term, the operationalization of Section 804 marks the beginning of the process to end U.S. trade protectionism in pharmaceuticals. Recently introduced legislation at the federal and state levels have called for the expansion beyond Canada of permissible wholesale importation from other high-income countries, such as those included in the MEDS Act.[xxxiv] [xxxv]

4.1.3. Section 801 and Multi-market Approved Drugs

Confusing as it may seem, the FDA has issued guidance, pursuant to Section 801 of the FDCA, for drug manufacturers to import and sell FDA-approved drugs — ones initially planned for sale in another country — at lower prices.[xxxvi] In the FDA’s guidance, these are called multi-market approved (MMA) products.[xxxvii] In drug manufacturing establishments in Europe, drugs are labeled for domestic European markets, not for the United States. Many of those drugs, apart from the labeling, are FDA-approved drugs and eligible under this pathway. There is no country limitation placed on manufacturers who import drugs into the United States.

Why would the same drug companies that already import many of their drugs, charging higher prices to American compared to Canadian or European wholesalers, lower their prices? According to the FDA’s guidance, drug manufacturers have told FDA personnel that they are sometimes locked into higher prices:

Recently, FDA has become aware that some drug manufacturers may be interested in offering certain of their drugs at lower costs and that obtaining additional NDCs for these drugs may help them to address certain challenges in the private market.”[xxxviii]

This new guidance appears to call the bluff of drug companies: it allows them to circumvent contracts more easily with third parties by creating new NDCs for the exact same drugs that were intended for sale outside the U.S. Those “challenges in the private market” pertain to drug price discount and rebate negotiations with private third parties, such as pharmacy benefit managers and other payers. All drugs have an NDC, and, attached to each NDC, a list price. By creating a new NDC for MMA drugs, manufacturers could lower the prices because the new NDC would not be part of any existing third-party discount or rebate contracts.

At the time of this writing, drug manufacturers have not brought a product to the US market using this new importation pathway.

This pathway, however, raises important questions about how many currently FDA-approved drugs could qualify as MMA products.

Many of the drugs assessed in “Not Made in the USA” fall into the category of MMA products. Some of the U.S.-sold drugs identified under FDA’s definition as “imported” are ones sold in other countries as well. If the manufacturers could make the same profits cutting out middlemen with lower prices in the U.S., then it is conceivable that this guidance will be used, but it will be done sparingly so and without great effect.

4.2. Allowing Personal Drug Importation

Unlike the importation pathways mentioned above, personal importation already benefits Americans.[xxxix] Safe personal drug importation occurs through programs offered in numerous self-insured U.S. municipalities, labor unions, and other organizations; patient assistance services, often referred to as “pharmacy storefronts,” offices where people get help to buy a lower cost drug from Canada and other countries; and properly credential international online pharmacies.[xl] Vastly lower drug prices in other countries explain why, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation survey, an estimated 20 million people in the U.S. had imported prescription drugs by 2016, a number that is likely higher.[xli] As the survey authors point out, it’s possible that some respondents didn’t want to go on record about their medicine purchases or having done something that may have been technically illegal.[xlii] Also, it does not account for older Americans who were importing prescription drugs before the advent of the Medicare Part D program and who had died by the time of the survey.

Lower-priced drugs are purchased in person by traveling to another country, or via mail order, often using online pharmacies.[xliii] Uniquely, personal drug importation can be permitted but, under most circumstances, is illegal under U.S. law.[2] The reality that tens of millions of individuals importing prescription drugs for their own use have never been prosecuted — or even charged — shows that the practice is effectively, or de facto, decriminalized.

A more accurate figure of how many people have imported a prescription drug for personal use is probably about 40 million over the past 20 years. That estimate extrapolates from a 2019 analysis in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) showing that 2.3 million people with a prescription for that medication personally imported a prescription drug because of cost.[xliv] That number does not account for people importing drugs each year who do not have a prescription, a practice that should be discouraged.

One example of a personal drug importation program authorized by a state government was launched by the Utah Public Employees Health Program in 2019. The state pays eligible employees to travel to Mexico to obtain prescription drugs at much lower cost.[xlv] It is limited to very expensive drugs that most affect the state’s budget.[xlvi] In 2020, about 10 state employees were given money for flights to Mexico, a $500 per trip bonus, and Utah’s government saved tens of thousands of dollars in medication costs.[xlvii]

Personal importation occurs despite the fact that the FDA has issued a largely blanket public warning against personal imports of lower cost drugs, even from Canada and other high-income countries.[xlviii] The FDA’s enforcement regime for personal drug importation can be metaphorically described as a yellow traffic light for pedestrians. The agency’s position, therefore, does not fully explain why only about 1.5% of Americans avail themselves each year of lower cost medicines from other countries. A huge deterrent is the false or misleading public information campaigns funded by pharmaceutical companies that warn people against it.[xlix] In the absence of those warnings, a far greater number of Americans would import prescription drugs, creating downward pricing pressures in the U.S. pharmaceutical market.[l]

While it has the statutory mandate to do so, the FDA does not regularly “allow” personal importation of prescription drugs to help Americans obtain lower prices.[li] However, the FDA sometimes refuses and destroys international prescription drug orders.[lii] Personally imported medicine often comes into the country via international mail facilities, where U.S. Customs and Border Protection screen packages.[liii] Over the past three years, due to greater congressional appropriations to curb opioid imports at international mail facilities, it appears that more Americans are seeing their prescription orders taken away.[liv]

Since it is no longer tenable to question the relative safety of drugs in Canada or Europe compared to the U.S., opponents of personal importation rely on threats surrounding the dangers from the Internet and the assumed inability of a consumer to find a licensed pharmacy outside the U.S. from which to purchase a more affordable prescription drug.[lv] PharmacyChecker.com plays a critical, private sector verification role in this respect by accrediting online pharmacies that process orders internationally filled by licensed pharmacies that require legitimate prescriptions.[lvi] Additionally, members of the Canadian International Pharmacy Association (CIPA) are recognized for providing safe international pharmacy services.[lvii] A public sector or non-profit initiative to provide those verification and information services, such as one led by the FDA, could help many more Americans benefit from safe personal drug importation.

4.2.1. Executive Orders on Personal Drug Importation

On July 24, 2020, the Trump Administration’s Executive Order on drug importation called for expressly permitting personal drug imports.[lviii] Under this EO, the FDA could assume an official role in identifying licensed pharmacies, including online pharmacies, and permit American consumers to order from them.

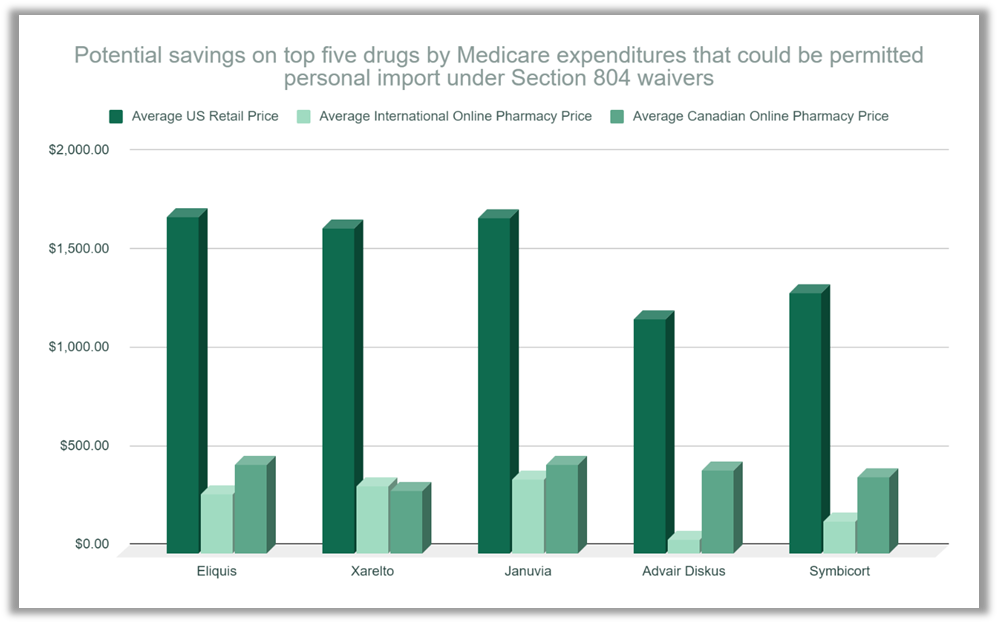

|

Source: PharmacyChecker Research, 2021

|

EOs on drug prices under the Trump administration were generally criticized for having political motivations and little potential for implementation or impact.[lix] The EO on personal drug importation does not fall into the latter category. As stated above, millions of Americans have already realized savings from personal drug importation; for many of them, it has meant taking a prescribed drug that they could not otherwise afford.[lx] Yet due to the federal restrictions and misinformation about the dangers of “foreign drugs,” the reach of personal drug importation has been limited.[3] [lxi] With the executive order still on the books under the Biden administration, the scope of its impact depends largely on the willingness of HHS to expand its use.

Based on the EO, HHS issued two requests for proposal (RFP) on September 24, 2020, calling on interested parties to formulate and submit for review new programs for safe personal drug importation.[lxii] [lxiii] One RFP on personal importation proposes that American consumers apply to HHS for individual waivers to obtain express permission to import.[lxiv] One requirement of the RFP is that the imported drugs would have to be dispensed from a licensed U.S. pharmacy, instead of directly from a licensed foreign pharmacy, limiting the potential benefits by creating a middleman. One of the comparative advantages of personal drug importation, compared to wholesale drug importation, is that there is no middleman to cut into potential savings.

Highly supportive of the conclusions found in “Not Made in the USA” on safety is the RFP’s list of countries from which personal importation would be permitted:

Under this pathway, individuals in the United States who have obtained waivers from the Secretary would be able to import certain FDA-approved prescription drugs from Australia, Canada, the European Union or a country in the European Economic Area, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, Switzerland, South Africa, or the United Kingdom (each an ‘Acceptable Foreign Source’).”

As “Not Made in the USA” shows, these are the countries in which the majority of expensive brand name drugs are manufactured. The key to the safety of personal importation is to ensure that the consumer is able to identify a licensed pharmacy in another country that requires a valid prescription and sells the same prescription drug they need at a much lower cost.[lxv]

The other RFP on personal importation called on HHS to create a pathway for the reimportation of insulin.[lxvi] This request was launched based on a declaration by the HHS Secretary that, due to high domestic insulin prices, imports were “required for emergency medical care.”[lxvii] That declaration was made under Section 801(d)(2) of the FDCA, the statute that prevents drug imports for commercial use (re-sale), except by the drug manufacturers or due to an emergency. This policy concept was curiously narrow to only include reimported insulin: insulin made in the U.S. and exported for sale in another country. Of the three main and difficult to afford insulin products sold in U.S. pharmacies, Lantus Solostar (Sanofi Aventis), Humalog (Eli Lilly), and Levemir (Novo Nordisk), only Humalog is made in the U.S.

4.2.2. RFPs Withdrawn but HHS is Open to New Ideas on Personal Drug Importation

In July of 2021, HHS withdrew the RFPs on personal drug importation but is considering alternative personal drug importation programs.[lxviii] By identifying the most efficient and safest channels for personal drug importation, federal and state governments, as well as non-profit and healthcare organizations, can greatly benefit patients who are unable or struggling to afford prescription drugs due to lack or inadequacy of health insurance.

“Not Made in the USA” data can help those who are working on drug importation programs, whether at the wholesale or personal importation level, by identifying the most expensive drugs and their countries of manufacture, along with the demonstrably substantial price discrepancies. The data in “Not Made in the USA” shows the degree to which the U.S. already relies on importation from the high-income countries identified. Creating FDA-approved pathways for personal imports from the countries identified in the RFP should be a priority.

4.3. Full, Open and Safe Parallel Trade in Pharmaceuticals Among High Income Countries

While new policy developments and federal rules have opened doors to importation programs that can help Americans obtain lower-cost drugs, the best path forward is for the federal government to expansively open trade in pharmaceuticals with high-income countries that have equally strong safety regulations to those of the United States.

Canada is too small and will not permit largescale, wholesale importation. Personal drug importation is of great value for individual consumers slipping through the healthcare system cracks. However, if that pathway is greatly expanded, it begs the question why we would not allow it at the wholesale level.

The European Union has open trade, referred to as parallel trade, in pharmaceuticals among member countries, despite opposition from drug manufacturers.[lxix] Economic analyses show that allowing parallel importation in the U.S. — from high-income countries, including wholesale and personal prescription drug imports— would substantially lower domestic drug prices.[lxx] Parallel trade is a market-based response to the monopolistic pricing effects of patents, and the differential ability of select markets to pay (e.g., less in Spain or Greece, more in France or Germany). According to its proponents:

...parallel imports are the only form of price competition during the period of patent protection of a medicine (called intra-brand competition). In other words, parallel trade in medicines creates competition in a business where patents provide the rights owner with a monopoly in every national market. This is good for the European economy, good for health care systems and good for patients.”[lxxi]

A successful model exists for this expansion. Strict regulatory protocols are in place for the safe distribution of pharmaceuticals throughout the European Union.[lxxii] U.S. regulatory reforms to allow for safe parallel importation would require a substantial effort led by the FDA with commensurate costs, but the costs would be minimal compared to the overall savings by government payors and patients over time.

As previously mentioned, safety arguments about drug quality against parallel trade in brand name drugs ring hollow. “Not Made in the USA” shows a majority of the expensive brand name drugs we use are made in the EU and other high-income countries. They also manufacture many generic drugs. The U.S. now has memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with all European Union member countries in which their respective drug regulatory authorities are viewed as equal in ability to enforce standards for the safe manufacture of high-quality prescription drugs. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the FDA has accepted more such third-party arrangements substituting for in person, foreign inspections.[lxxiii]

The extent to which our drug supply already relies on importation is enough to warrant the reforms necessary to allow businesses other than drug manufacturers the ability to import drugs at lower prices from countries beyond Canada, specifically from the European Union. Thus, creating a regulatory framework for parallel trade in pharmaceuticals is the task at hand.

4.3.1. The Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA) is Not an Excuse Against Parallel Importation

Since the passage of the Drug Quality and Safety Act of 2013 (DQSA), the U.S. has embarked on and is far along in the process of mandating electronic track and trace systems for FDA-approved products from manufacturer to wholesaler, to pharmacy.[lxxiv] The goal is to “enhance FDA’s ability to help protect patients from exposure to drugs that may be counterfeit, stolen, contaminated, or otherwise harmful.”[lxxv] One of the central arguments made by respected opponents of drug importation under Section 804 is that it is not compatible with the Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA), Title II of the DQSA.[lxxvi] Yet even those arguments seem to simply give cover to the drug companies’ drive to prevent “diversion,” legal or illegal. The pharmaceutical industry believes that legal parallel trade in the EU is a form of drug “diversion.”[lxxvii] Not surprisingly, in the DSCSA, an “illegitimate” drug is one that is “is counterfeit, diverted, or stolen.”[lxxviii] Thus, in some respect, the purpose of the DSCSA is to help drug manufacturers control their distribution channels to maximize profits.

The main argument against importation today focuses on the DSCSA-required serialization of a drug’s package. Two noted industry experts, Adam J. Fein and Dirk Rodgers, write:

Products sold for the Canadian market lack a DSCSA-compliant standardized numerical identifier. This would irreparably break the necessary DSCSA tracking history, making the products permanently unsellable in the U.S.”

There is a circular logic behind those statements, which can confuse policymakers and the public. Fein and Rodgers are saying that if the Health Canada-approved drugs do not have DSCSA identifiers, then they are unsellable in the U.S. because the DSCSA makes it so. True, but what does that have to do with the safety of those drugs? Drugs sold in Canadian pharmacies don’t have DSCSA identifiers, but that does not make those drugs any less safe and effective than ones sold in U.S. pharmacies. For example, the drug Januvia (sitagliptin), made in the UK and Italy, is sold in Canada and the United States. The exact same Januvia is labeled differently for each market. Even well-regarded opponents of importation, such as former FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb, MD, concede that the safety of the actual drug products in Canada is not in any doubt.[lxxix] It is the distribution that scares many importation opponents. Supporters of importation contend that the DSCSA already accommodates prescription drug importation because many foreign factories making drugs for the U.S. market, the ones analyzed in this report, must be DSCSA-compliant.[lxxx] This discussion about whether importation proposals now on the table can comply with the DSCSA detracts from the real issue, which is whether the DSCSA should be updated to allow for parallel drug importation.

If the answer is yes, then we should turn our attention to the European Union, which has its own version of track and trace that is arguably superior to the DSCSA.[lxxxi] Created under the EU Falsified Medicines Directive, all prescription drugs sold in the EU are traceable back to the manufacturers and scanned at the unit level, before dispensing to the patient.[lxxxii] The DSCSA lacks this scanning requirement and does not track at the unit level, which leaves products containing larger wholesale quantities vulnerable to tampering and adulteration, a problem of which the FDA is well aware.[lxxxiii] Furthermore, implementation of DSCSA to date has not prevented counterfeit drugs from entering the “legitimate” supply chain, as evidenced by a major breach earlier this year where fake versions of Gilead’s HIV drugs, Biktarvy and Descovy, reached U.S. pharmacy shelves.[lxxxiv] That breach did not occur in the EU.

The U.S. already recognizes the safety of drugs made in the EU. We must also recognize that the EU’s system of parallel trade in pharmaceuticals is vigorously regulated for safety. There is an honest debate about how to integrate new pathways for drug importation as a means to lower prices that will maintain safe distribution channels. In contrast, it is dishonest to assert that it cannot be done.

4.4. End the FDA’s Trade Protectionist Regulatory Regime

The FDA is a global pioneer and leader among drug regulatory authorities, but it can no longer be viewed as superior to all other drug regulatory authorities in terms of its oversight role of drug manufacturing, safety, and quality. That pedestal is promoted by the pharmaceutical industry, which needs to maintain the public perception of FDA’s superiority to prevent price competition from parallel trade. In its myriad efforts to oppose drug importation legislation, for decades, the industry has pushed the narrative of the FDA as the “gold standard.” A page on the website of the Pharmaceutical Researchers and Manufacturers of America called “The Dangers of Drug Importation” states:

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is the gold standard when it comes to regulating the safety of our medicine supply. Medicines that enter the United States through importation will not be subject to these same strong standards and, as a result, counterfeit, substandard or diverted, repackaged and adulterated drugs could be introduced into our secure drug supply chain.”[lxxxv]

The FDA’s position on importation is to a large extent a product of the lobbying power of the pharmaceutical industry.[lxxxvi] [lxxxvii] Drug industry groups' lobbying efforts influence Congress to create laws and regulations favorable to its business models and, in turn, ensure that the FDA enforces regulations that most protect it.[lxxxviii] Thus, not only is the FDA a victim of “industry capture,” but it bureaucratically perpetuates a self-regard as the “gold standard” in drug regulation and safety.[lxxxix] This dynamic is made possible by the unique regulatory arena of prescription drug manufacturing and marketing, where the regulator and regulated appear to have the same goal: the creation and distribution of as many safe and effective drugs to help as many people as possible.[xc] Thus, even for those who insist that profit is the only goal of the pharmaceutical industry, the point here is not the sincerity of the industry but understanding the reputation it strives for and needs.[xci] For this reputation, the industry looks to the FDA.

This bureaucratic paradigm, discussed in detail below, one created by the industry, is now endemic to the FDA’s mission and helps maintain a high-priced captive market for prescription drugs. This framework of analysis was developed in “Reputation and Authority: The FDA and the Fight over U.S. Prescription Drug Importation” by Thomas J. Bollyky and Aaron S. Kesselheim.

FDA’s public opposition to legislation and regulatory reforms on importation often relies on the argument that the agency does not have the resources to oversee the kinds of importation pathways that could lead to lower prices, while still protecting public health, and that the resources needed are too great.[xcii] Bollyky and Kesselheim explore how the FDA’s position on importation is less about resources and public health and more about self-protective bureaucracy. They deconstruct what I believe are the bureaucratic consequences of the pharmaceutical industry’s lobbying power in explaining the FDA’s opposition to importation:

[...]FDA officials describe themselves as “the gold standard” for drug review — more thorough and rigorous about regulation than their counterparts — and, until recently, as able to fulfill their core institutional mandates without the cooperation of foreign counterparts.”[xciii]

Thus, while the FDA has agreed to sign MOUs with many foreign drug regulators, accepting their inspections in lieu of its own, it will not accept the equivalence determinations of those same regulators because, according to Bollyky and Kesselheim, that would threaten the FDA’s reputation and its funding. They state:

…[T]he FDA’s limited use of equivalence determinations is unsurprising. In contrast to the European Commission (‘EC’), where its Directorate-General for Industry and Enterprise is charged with coordinating regulatory protection and trade, the FDA has the consolidated statutory authority as the gatekeeper for ensuring the safety, quality, and efficacy of medicines. To sustain that authority and its funding, the FDA depends on its reputation for protecting consumers from unsafe drugs.”

[...] FDA has resisted initiatives that might undermine that reputation and subordinate its gatekeeping mission to other policy objectives, such as lowering drug prices or facilitating trade.”[xciv] Emphasis added.

Instead of “trade,” the authors could have used the word “importation.”

Unfortunately, Bollyky and Kesselheim accept the agency’s position as a fait accompli and do not challenge its substantive flaws. They appear to recognize that the agency is not necessarily the Gold Standard anymore, but, because of its reputation and authority and, thus, its refusal to accept foreign drug approvals, they recommend a new permitted importation channel that they believe will not challenge the FDA:

[...]we suggest that a mechanism for U.S. prescription drug importation could be successfully used to reduce generic drug shortages and extreme price hikes among off-patent drugs that function like product shortages[...]”[xcv]

Their recommendation would allow imports of lower cost, foreign versions of FDA-approved drugs, mostly when a shortage exists in the U.S., but also in cases of when off-patent drugs are subject to severe price hikes. An example of such a drug is Gleostine, a brand name version of an FDA-approved drug called lomustine, an off-patent medication that treats cancer. These are drugs for which companies try to exploit marketing exclusivity rules to corner the market. In this case, a company called Next Source Biotechnology LLC secured these rights and launched Gleostine in 2016 with a price tag of about $750/pill. Before that launch, a Bristol Myers Squibb brand version called CeeNU was sold in

Bollyky and Kesselheim’s approach does not address the main cost driver, which is patented drugs. Most expensive among those are biologics. According to a RAND Corporation analysis, prices for biologics in the U.S. are almost three times higher on average than in other OECD countries.[xcvii] While that is lower than the overall price differentials estimated by RAND, with U.S. prices being 3.44 times higher, the impact on overall spending on biologics is greater.[xcviii] Biologics usually cost between $10,000 - $30,000 and in some cases exceed $500,000 a year.[xcix] Almost all new patented cancer drugs are over $100,000.[c]

The FDA’s leadership was famously cemented in the early 1960s when an FDA drug reviewer, Dr. Frances Kelsey, boldly prevented the approval of thalidomide in the U.S..[ci] Thalidomide, used as a drug to treat morning sickness, was found to cause birth defects in babies born to women who had taken the drug while pregnant. It is estimated to have caused deformities in 10,000 babies worldwide.[cii] Until recently, the mythologizing narrative held that only 17 babies in the U.S. were known to be affected.[ciii] Those cases were the result of the drug company distributing samples to doctors who gave them to their patients even though the drug was not approved.[civ] An investigative article from 2020 by Katie Thomas at the New York Times indicates a much larger affected population.[cv]

This history is often presented to showcase the superiority of U.S. drug regulators.[cvi] Dr. Kelsey’s heroic efforts speak for themselves, but it was really subsequent lawmaking by Congress that forced the FDA to conduct much more stringent drug evaluations before approving new drugs for the market.

What is not often stated is that these same reforms to improve drug regulation happened in many other countries, too.[cvii] History also shows that U.S. drug companies lobbied to prevent these changes as well. An article published on the FDA’s website about the agency’s history clarifies this point:

As a result of the worldwide thalidomide disaster, countries around the world, including the United States, updated their drug regulatory systems and statutes. ‘In next to no time,’ recalled Frances Kelsey, ‘the fighting over the new drug laws that had been going on for five or six years suddenly melted away, and the 1962 amendments were passed almost immediately and unanimously.’”[cviii]

We can recognize, simultaneously, the FDA’s innovative success and the growth of foreign drug regulatory authorities. The latter now have comparable capacities for drug evaluation and may even be better at this point in regulation of the production of prescription drugs. In doing so, we can move beyond a protected marketplace where a mistaken presumption of FDA superiority helps keep drug prices high.

The global supply chains for brand name pharmaceuticals in other high-income countries allow for dynamic and safe parallel trade that would serve to substantially lower drug prices in the United States and equalize them across high income countries. The extent to which our drug supply relies on importation currently is enough to warrant serious reforms in the U.S.; that is to allow businesses, other than drug manufacturers, the ability to import drugs at lower prices from countries beyond Canada, most importantly from the European Union.

It is no longer defensible for the FDA to prevent this on the basis of drug safety.

4.5. Policy Recommendations for the Federal Government

This final section includes policy recommendations for the federal government given the findings in “Not Made in the USA.”

- Require drug manufacturers to clearly identify the country where a drug’s API and FDF originated.

Pharmaceuticals to make prescription drugs sold in the U.S. come from all over the world. This paper has shown that manufacturer labels already provide information making it possible to assess where drugs come from. However, it should be more straightforward for patients, providers, and policymakers to know from where the active pharmaceutical ingredients and finished formulations of prescription drugs purchased in U.S. pharmacies come. Also, the country in which a drug is merely labeled and packaged, if different from the place where the actual drug is manufactured, should not be identified as the place of manufacture, as is currently permissible under the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

To accomplish this, Congress should amend Section 502 of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, 21 USC 352: Misbranded drugs and devices. A drug label should make it clear to a patient where the drug’s API and its finished formulation were manufactured.

Current law requires that a prescription drug label include the “name and place of business of the manufacturer, packer, or distributor…”

New legislation should require adding the following language: “and the countries of origin of the active pharmaceutical ingredients and the finished drug formulation and the country where the drug was labeled and packaged.” Under these changes, the relevant Code of Federal Regulations (21CFR201) would state:

A drug or drug product (as defined in § 320.1 of this chapter) in finished package form is misbranded under section 502 (a) and (b)(1) of the act if its label does not bear conspicuously the name and place of business of the manufacturer or distributor; the countries of origin of the active pharmaceutical ingredients and the finished drug formulation; and the country where the drug was labeled and packaged.”

- Mandate through legislation the publication of an annual FDA report showing clear and accurate data on where our drugs are made.

Congress should amend the FDCA to require an annual report from the FDA so that Americans know what percentage of FDA-approved drugs are not made domestically. This would not require the FDA to know the volumes of pharmaceutical imports. The report would simply list the name of every FDA-approved drug; its National Drug Code; the country its API or APIs are made in; the country of its final formulation; and the country where it is packaged for final dispensing.

- Through legislation, expressly allow importation of brand name drugs by companies, other than their manufacturers, from countries known to have similarly strong pharmaceutical regulations as the U.S., subject to rational regulatory safeguards.

Under current law, Section 804 of the FDCA, importation of commercial quantities of prescription drugs for re-sale without the authorization of the manufacturer is only permitted from Canada. Its relatively small size to the U.S., 38 million compared to 330 million, precludes long-term and meaningful parallel trade in pharmaceuticals with the United States. In contrast, the combined markets of Canada, Japan, the European Union, and the United Kingdom, have 667 million people — twice the U.S. population. If other high-income countries with strong pharmaceutical regulations are added, including Australia, Israel, New Zealand, Singapore, and Switzerland, the relevant market size is almost 700 million. Those regions and countries are also where most of our brand name drugs are manufactured. Section 804 must be amended to allow non-manufacturers importation from those countries, too.

The amendment to allow imports from this greater network of countries would be specific to brand name drugs manufactured in the listed countries.

Currently, Section 804 precludes the importation of biologics. The most expensive category of medical products on the market, biologics represent about 40% of all pharmaceutical expenditures,[cix] but only about 2% of prescriptions written.[cx] As previously mentioned, wholesale prices for biologics are on average almost three times higher in the U.S. than in the OECD.[cxi] Thus, Section 804 must be amended to permit the importation of biologics.

Ostensibly, the preclusion of biologics in Section 804 was due to the greater challenges in safe distribution of what are referred to as “large molecule” pharmaceuticals that are produced with living organisms and therefore require special technology to ship under temperature controls. Today, U.S. pharmacy benefit managers, such as Optum,[cxii] are already actively importing biologics, albeit under the authorization and with the cooperation of the manufacturers. A federal rule should require wholesale importers of biologic drugs to meet or exceed manufacturer specifications for safe, international shipping. Optum’s marketing materials provide a roadmap to develop the standard).[cxiii]

The current federal rule allowing wholesale importation under Section 804, requires that the U.S. importer only imports from a wholesaler that received the products for import directly from the manufacturer. This rule makes it easier for drug manufacturers to use inventory management to prevent unwanted distribution of their products from lower to high priced markets. The rule should be revised to allow the U.S. importer to import from a secondary wholesaler, as long as that wholesaler received the products from the wholesaler that first received the products from the manufacturer. This revision would maintain a closed distribution channel while allowing for the development of a competitive marketplace in pharmaceutical trade, similar to the European Union.

- Remove barriers and provide guidance to assist individual patients who seek to import brand name drugs pursuant to a valid prescription.

The Secretary of Health and Human Services is already seeking new ideas on expanding personal drug importation to help patients access lower drug prices internationally.[cxiv]

The FDCA is very flexible to allow personal importation of lower-cost medicines. A few million Americans each year already import lower-cost medicine for personal use. While they are not charged or prosecuted for illegal imports, individuals purchase medicine, often over the Internet within a grey marketplace, receiving conflicting messages from regulators, industry-sponsored and non-profit organizations on what they should and shouldn’t do.

Organizations like PharmacyChecker and the Canadian International Pharmacy Association provide guidance to patients and healthcare providers for those who choose to import medicine for personal use. Those private sector solutions are helpful, but a publicly or non-profit funded effort is needed to bring greater awareness and stakeholder acceptance of safe personal drug importation.

To maximize the utility of personal drug importation as a safe and accepted channel for drug affordability, the following is proposed:

-

- Create an HHS task force with a diverse set of stakeholders to review best practices in safe personal drug importation and create FDA recommendations to the public. As part of its mandate, the task force would identify all current programs and channels of personal drug importation, assessing their strengths and weaknesses.

-

- Revise the FDA’s public communications to include useful recommendations for patients who choose to import a lower cost medicine for personal use and clarify that the agency will not prevent the personal import of a brand name drug from licensed pharmacies in Australia, Canada, the European Union, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, Switzerland, Singapore, and the UK.

As a general model, the U.S. can look to Australia, in which personal importation is expressly legal and the government provides warnings and guidance.[cxv] As Australians do not face the same problems as Americans do with drug affordability, Australians’ necessity for personal importation is not as widespread. Thus, the FDA would need to create more robust warnings and guidelines for patients in the United States.

- Instead of reactionary, mercantilist policies to bring drug manufacturing home, pursue greater global collaboration and coordination towards an international agreement to better regulate and ensure the safe manufacture and high quality of APIs.[cxvi]

APIs are made all over the world and shipped globally to different drug companies for the manufacture of FDFs. This global competition has meant much lower cost generic drugs worldwide, including in the U.S. For reasons of national security, whether due to geopolitical tensions with China or reliance on foreign supplies during the pandemic, there is a new rallying cry for greater autarky with pharmaceuticals. A more longstanding, and less politically charged issue is that, for over 20 years, the FDA has been criticized for its inability to keep up with federal requirements on inspections and oversight of global API manufacturers.

In terms of national security, the U.S. should identify the greatest vulnerabilities and create practical contingency plans involving alternative suppliers or ramping up domestic production. The FDA has reported to Congress on the extent of our vulnerabilities, and they are not as great as the rhetoric on this issue. China accounts for 13% of all FDA registered API manufacturers, a significant but not overwhelming figure. As a matter of national defense policy, we need to identify alternative suppliers for those pharmaceutical ingredients and appropriate special funding and production plans to ramp up domestic manufacturing of the most critical pharmaceuticals.

Outside the above-mentioned national security issues, we must accept the reality of global pharmaceutical manufacturing. To maximize safety and minimize cost, the U.S. should set clear goals for international harmonization on API standards, cGMP, and distribution. The European Medicines Agency is already leading this effort, with the FDA as a participant.[cxvii] FDA’s MRAs with all EU countries on drug manufacturing, finalized in 2019, occurred because the FDA knows that the future lies in globally accepted standards and even shared regulatory authority.

Efforts to harmonize API quality standards have been ongoing for 20 years through the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH), the Pharmaceutical Inspection Co-operation Scheme, and the World Health Organization. The FDA publishes a questions-and-answers document for the regulated industry called “Q7 Good Manufacturing Practice Guidance for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients” that is the product of those efforts.[cxviii]

The next step is for the FDA to prioritize working with those international forums and counterpart national drug regulators to create a global regulatory approval scheme for API manufacturers. The goal is for an API manufacturer, whether in Mumbai, Minneapolis, or Munich, to gain approval for international distribution based on one high standard. This will create efficiencies, improve safety, and reduce costs for American taxpayers.

[1] The main author of the model state drug importation bill is public policy analyst Jane Horvath.

[2] In Section 804 of the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, Congress “declares” that the Secretary of Health and Human Services, which administratively would devolve to the FDA commissioner, “should” permit otherwise prohibited drug importation as long as the importers are individuals obtaining prescription drugs for their own use that are not an “unreasonable risk.”

[3] Roger Bate writes: “A debate about how to provide cheaper drugs for these Americans while protecting US businesses is entirely legitimate. But it is a debate that the industry does not think it can win. Instead of engaging in serious discussion, pharma companies and myriad industry-funded groups have scared Americans into believing that drugs from overseas pharmacies are inherently dangerous.”

[i] Drug importation. (n.d.). PhRMA Org | PhRMA. https://www.phrma.org/policy-issues/drug-importation

[ii] National Association of Chain Drug Stores. (2019, January 18). Patient safety key as NACDS and APhA oppose prescription drug importation. NACDS. https://www.nacds.org/news/patient-safety-key-as-nacds-and-apha-oppose-prescription-drug-importation/

[iii] Salant, S., & Levitt, G. (2021, February 17). The one-two punch to knock out high drug prices. The Hill. https://thehill.com/opinion/healthcare/539064-the-one-two-punch-to-knock-out-high-drug-prices

[iv] Drug importation, supra note 79.

[v] Elgin, B. (2019, October 23). Sheriffs’ ads slammed drug imports, and big pharma helped pay the tab. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2019-10-23/big-pharma-helped-fund-sheriffs-ad-blitz-against-drug-imports

[vi] Here's how the drug industry funds 'experts' to discredit efforts to lower prices. (2019, February 19). Tarbell. https://tarbell.org/2019/02/heres-how-the-drug-industry-funds-experts-to-discredit-efforts-to-lower-prices2/

[vii] The hidden hand: big pharma's influence on patient advocacy groups. (2021). Patients For Affordable Drugs. https://patientsforaffordabledrugs.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/06-28-21_P4AD_HiddenHandReport_V24.pdf

[viii] Levitt, supra note 11.

[ix] Keeping international pharmacies under a cloud. (2018, May 2). Tarbell. https://tarbell.org/2018/05/keeping-international-pharmacies-under-a-cloud/

[x] The partnership for safe medicines. (n.d.). PolitiFact. https://www.politifact.com/personalities/partnership-safe-medicines/

[xi] H.R.4461 - Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2001. (2000). United States. Congress. House. https://www.congress.gov/bill/106th-congress/house-bill/4461?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22cite%3APL106-387%22%5D%7D&s=1&r=1

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] H.R.1 - 108th Congress (2003-2004): Medicare prescription drug, improvement, and modernization Act of 2003. (2003, December 8). https://www.congress.gov/bill/108th-congress/house-bill/1

[xiv] Increasing drug importation to lower prices for American patients (E.O. 13938). (2020, July 29). Executive Office of the President. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/07/29/2020-16624/increasing-drug-importation-to-lower-prices-for-american-patients

[xv] Adams, K. (2020, September 25). FDA, HHS allow states to import drugs from Canada. Becker's Hospital Review - Healthcare News. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/pharmacy/fda-hhs-allow-states-to-import-drugs-from-canada.html

[xvi] Importation of prescription drugs (85 FR 62094 ). (2020, October 1). Food and Drug Administration, Health and Human Services (HHS). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/10/01/2020-21522/importation-of-prescription-drugs

[xvii] Galewitz, P. (2021, May 28). Biden administration signals it’s in no rush to allow Canadian drug imports. Kaiser Health News. https://khn.org/news/article/biden-administration-signals-its-in-no-rush-to-allow-canadian-drug-imports/

[xviii] Ibid.

[xix] Importation of prescription drugs, 21 U.S. code § 384: (2011). https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCODE-2011-title21/USCODE-2011-title21-chap9-subchapVIII-sec384

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Galewitz, supra note 95.

[xxii] Model legislation and contracts – the national academy for state health policy (importation). (n.d.). The National Academy for State Health Policy. https://www.nashp.org/policy/drug-pricing-center/model-legislation/#toggle-id-6

[xxiii] Horvath, J. (2019, June 27). States are using drug importation to lower costs and provide safe access to drugs. Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2019/states-are-using-drug-importation-lower-costs-and-provide-safe-access-drugs

[xxiv] Galewitz, supra note 93.

[xxv] Increasing drug importation, supra note 92.

[xxvi] Roy, A., & The Apothecary. (2019, March 8). Biologic medicines: the biggest driver of rising drug prices. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/theapothecary/2019/03/08/biologic-medicines-the-biggest-driver-of-rising-drug-prices/?sh=6019fbed18b0

[xxvii] Increasing drug importation, supra note 92.

[xxviii] Ibid.

[xxix] Harris, G. (2003, August 7). Pfizer moves to stem Canadian drug imports (Published 2003). The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/08/07/business/pfizer-moves-to-stem-canadian-drug-imports.html

[xxx] Comments on the notice of proposed rulemaking concerning importation of prescription drugs. Docket No. – FDA-2019-N-5711 Federal Register Vol. 84, No 246, 70796. (2019). Horvath Health Policy. https://www.regulations.gov/document/FDA-2019-N-5711-1221

[xxxi] Health Canada. (2020, November 28). Canada announces new measures to prevent drug shortages. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2020/11/canada-announces-new-measures-to-prevent-drug-shortages.html

[xxxii] Ibid.

[xxxiii] Bollyky, T., & Kesselheim, A. S. (2020). Reputation and authority: the FDA and the fight over U.S. prescription drug importation. Vanderbilt Law Review, 73(5). https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4405&context=vlr

[xxxiv] Senate - Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions. (2021, March 23). S.920 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): Affordable and safe prescription drug importation act. Congress.gov | Library of Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/920/cosponsors?q=%7B%22search%22%3A%5B%22drug+importation%22%5D%7D&r=3&s=1

[xxxv] A bill for an act concerning expanding the Canadian prescription drug101 importation program to include prescription drug102 suppliers from nations other than Canada upon the103 enactment of legislation by the united states congress104 authorizing such practice. (2019). First Regular Session Seventy-third General Assembly - State of Colorado. https://leg.colorado.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2021A/bills/2021a_123_eng.pdf

[xxxvi] Importation of certain FDA-approved drugs, biologics, comb. Products. (2020, October 1). U.S. Food and Drug Administration Guidance for Industry. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/importation-certain-fda-approved-human-prescription-drugs-including-biological-products-and

[xxxvii] Ibid.

[xxxviii] Ibid.

[xxxix] Wolfson, B. J. (2019, August 20). Shopping abroad for cheaper medication? Here’s what you need to know. California Healthline. https://californiahealthline.org/news/shopping-abroad-for-cheaper-medication-heres-what-you-need-to-know/

[xl] Galewitz, P. (2019, June 28). Trump has blessed states’ exploration of importing drugs. Will it catch on? Kaiser Health News. https://khn.org/news/states-proposals-import-cheaper-drugs-trump-support-experiment/

[xli] Bluth, R. (2016, December 20). Faced with unaffordable drug prices, tens of millions buy medicine outside U.S. Kaiser Health News. https://khn.org/news/faced-with-unaffordable-drug-prices-tens-of-millions-buy-medicine-outside-u-s/

[xlii] Ibid.

[xliii] Ibid.

[xliv] Hong, Y., Hincapie-Castillo, J. M., Xie, Z., Segal, R., & Mainous, A. G. (2020). Socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of US adults who purchase prescription drugs from other countries. JAMA Network Open, 3(6), e208968. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.8968

[xlv] Whitehurst, L. (2020, February 9). Utah sends employees to Mexico for lower prescription prices. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/wireStory/utah-sends-employees-mexico-lower-prescription-prices-68861516

[xlvi] Ibid.

[xlvii] Helmore and agencies, E. (2020, February 11). Utah cuts healthcare costs by flying employees to Mexico for prescriptions. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/feb/11/utah-cuts-healthcare-costs-flying-employees-mexico-prescription-drugs

[xlviii] Vedantam, S. (2012, April 6). FDA's stance on online pharmacies may go too far, study says. NPR.org. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2012/04/06/150151885/fdas-stance-on-online-pharmacies-may-go-too-far-study-says

[xlix] Levitt, G. (2015). Online pharmacies, personal drug importation and public health: ill-considered enforcement prevents access to safe and affordable medication. GAO Report on Internet Pharmacies Can Mislead Lawmakers and the Public about International Online Pharmacies. PharmacyChecker.com. https://cdn.pharmacychecker.com/pdf/online-pharmacies-personal-drug-importation-public-health.pdf

[l] Salant, S. (2021). Arbitrage deterrence: a theory of international drug pricing. resources for the future working paper.

[li] Levitt, G. (2018, October 5). Personal drug importation is protected by Congress. PharmacyChecker Blog. https://pharmacycheckerblog.com/personal-drug-importation-is-protected-by-congress

[lii] Galewitz, P. (2020, April 20). Amid pandemic, FDA seizes cheaper drugs from Canada. Kaiser Health News. https://khn.org/news/amid-pandemic-fda-seizes-cheaper-drugs-from-canada/

[liii] International mail facilities. (2020, November 23). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/industry/import-basics/international-mail-facilities

[liv] Levitt, G. (2021, August 31). Access to safe, affordable medication is a casualty of the war on opioids. The Hill. https://thehill.com/opinion/healthcare/570124-access-to-safe-affordable-medication-is-a-casualty-of-the-war-on-opioids

[lvi] Bate, supra note 12.

[lvii] Ibid.

[lviii] Increasing drug importation, supra note 92.

[lix] Knight, V. (2020, August 26). Trump again claims he’s bringing down drug prices, but details of how are skimpy. Kaiser Health News. https://khn.org/news/president-trump-once-again-claims-hes-bringing-down-drug-prices-but-details-of-how-are-skimpy/

[lx] Bluth, supra note 119.

[lxi]. Bate, supra note 12.

[lxii] Requests for proposals for insulin reimportation and personal prescription drug importation; Withdrawal (86 FR 36283 ). (2021, July 9). Food and Drug Administration. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/07/09/2021-14637/requests-for-proposals-for-insulin-reimportation-and-personal-prescription-drug-importation

[lxiii] Request for proposals regarding waivers for individual prescription drug importation programs. (2020). HHS.gov. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/individual-prescription-drug-importation-programs.pdf

[lxiv] Ibid.

[lxv] Bate, supra note 12.

[lxvi] Request for proposals regarding insulin reimportation programs. (2020, September 24). HHS.gov. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/insulin-reimportation-programs.pdf

[lxvii] Increasing drug importation, supra note 92.

[lxviii] Requests for proposals, supra note 140.

[lxix] What is parallel trade. (2020, February 6). Affordable medicines Europe. https://affordablemedicines.eu/what-is-parallel-trade/

[lxx] Salant, supra note 125.

[lxxi] What is parallel trade, supra note 143.

[lxxii] European Union compliance. (n.d.). Tracelink. https://www.tracelink.com/solutions/compliance-track-and-trace/european-union-compliance

[lxxiii] U.S. department of health and human services, food and drug administration, center for drug evaluation and research, center for biologics evaluation and research, & office of regulatory affairs. (2020, August). Manufacturing, supply chain, and drug and biological product inspections during COVID-19 public health emergency questions and answers guidance for industry. https://www.fda.gov/media/141312/download

[lxxiv] Drug supply chain security act (DSCSA). (2021, October 25). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-supply-chain-integrity/drug-supply-chain-security-act-dscsa

[lxxv] Ibid.

[lxxvi] Fein, A. J., & Rodgers, D. (2019, July 11). State drug importation laws undermine the process that keeps our supply chain safe. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2019/07/11/state-drug-importation-laws-undermine-supply-chain-safety/

[lxxvii] European patient safety and parallel pharmaceutical trade– a potential public health disaster? (2007). European Alliance for Access to Safe Medicines. https://eaasm.eu/wp-content/uploads/Patient_safety_report_FINALVERSIONp1.pdf

[lxxviii] Drug supply chain security act. title ii of the drug quality and security act. sec. 581: definitions. (2014, December 16). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-supply-chain-security-act-dscsa/title-ii-drug-quality-and-security-act

[lxxix] Testimony by Scott Gottlieb, MD, former FDA Commissioner, before the House appropriations subcommittee on agriculture, rural development, food and drug administration, and related [Video]. (2019, March). United States House Appropriations Committee. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KyTCV9nJxLE

[lxxx] Horvath, J. (2019, July 16). State drug importation programs will work with the FDA. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2019/07/16/state-drug-importation-programs-fda/

[lxxxi] Souza, C. (2020, November 2). Comparing the DSCSA and the EU/FMD. TrackTraceRX Blog. https://blog.tracktracerx.com/comparing-dscsa-eufmd

[lxxxii] Ibid.

[lxxxiii] Rodgers, D. (2019, February 16). FDA hammer comes down on McKesson for DSCSA violations – RxTrace. RxTrace. https://www.rxtrace.com/2019/02/fda-hammer-comes-down-on-mckesson-for-dscsa-violations.html/

[lxxxiv] Liu, A. (2021, August 6). Gilead cracks down on fake versions of popular HIV drugs Biktarvy, Descovy being sold at US pharmacies. FiercePharma. https://www.fiercepharma.com/pharma/fake-versions-popular-hiv-drugs-biktarvy-descovy-are-sold-at-pharmacies-gilead-warns

[lxxxv] The dangers of drug importation. (2020, September 30). PhRMA Org | PhRMA. https://www.phrma.org/cost-and-value/the-dangers-of-drug-importation

[lxxxvi] Asif Ismail, M. (2005, July 7). Drug lobby second to none: How the pharmaceutical industry gets its way in Washington. Center for Public Integrity. https://publicintegrity.org/health/drug-lobby-second-to-none/

[lxxxvii] Agency lobbying profile: Food & Drug Administration. (2019). OpenSecrets. https://www.opensecrets.org/federal-lobbying/agencies/summary?cycle=2019&id=135

[lxxxviii] Tankersley, supra note 76.

[lxxxix] Bollyky, supra note 111.

[xc] Bernstein, A., & Bernstein, J. (2006). The information prescription for drug regulation. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.902160

[xci] Ibid.

[xcii] Carmona, R. H. (2005). Report of the HHS task force on drug importation. testimony of Richard H. Carmona before the special committee on aging, United States Senate, one hundred ninth Congress, first session, Washington, DC, January 26, 2005. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.aging.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/hr135rc.pdf

[xciii] Bollyky, supra note 111.

[xciv] Ibid.

[xcv] Ibid.

[xcvi] Levitt, G. (2018, January 24). Cancer drug lomustine sold in Canada for 97% cheaper. PharmacyChecker Blog. https://pharmacycheckerblog.com/cancer-drug-lomustine-sold-canada-97-cheaper

[xcvii] Mulcahy, supra note 40.

[xcviii] Mulcahy, A. W. (2021, January 28). Prescription drug prices in the United States are 2.56 times those in other countries. RAND Corporation provides objective research services and public policy analysis | RAND. https://www.rand.org/news/press/2021/01/28.html

[xcix] Chen, B. K., Yang, Y. T., & Bennett, C. L. (2018). Why biologics and biosimilars remain so expensive: despite two wins for biosimilars, the Supreme Court’s recent rulings do not solve fundamental barriers to competition. PubMed.gov, 78(17), 1777-1781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-018-1009-0

[c] Rimer, B. K. (2018, March 15). The imperative of addressing cancer drug costs and value. National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2018/presidents-cancer-panel-drug-prices

[ci] Junod, S. W. (2008). FDA and clinical drug trials: a short history. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/media/110437/download

[cii] Vargesson, N. (2015). Thalidomide-induced teratogenesis: History and mechanisms. Birth Defects Research Part C: Embryo Today: Reviews, 105(2), 140-156. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdrc.21096

[ciii] Thomas, K. (2020, March 23). The unseen survivors of thalidomide want to be heard (Published 2020). The New York Times - Breaking News, US News, World News and Videos. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/health/thalidomide-survivors-usa.html?searchResultPosition=1&fbclid=IwAR08WLKPkx7jje79EfHsULCvMoSBIg4drG9QcmOj5wl_6YymqkxCn8O8jYs

[civ] Junod, supra note 179.

[cv] Thomas, supra note 181.

[cvi] Gaffney, A. (2012, October 10). FDA marks half-century of regulation based on safety, efficacy. Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society | RAPS. https://www.raps.org/regulatory-focus%E2%84%A2/news-articles/2012/10/fda-marks-half-century-of-regulation-based-on-safety,-efficacy

[cvii] Ibid.

[cviii] Ibid.

[cix] Aitken, M. (2020, March 9). Biologics market dynamics: setting the stage for biosimilars [PDF]. IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_events/1568297/aitken_-_biologics_market_dynamics_setting_the_stage_for_biosimilars_slides.pdf

[cx] Roy, supra note 104.

[cxi] Mulcahy, supra note 40.

[cxii] Six thoughts: Temperature-controlled shipping. (n.d.). Health Services Innovation Company | Optum. https://www.optum.com/business/resources/library/cool-thoughts-shipping-sensitive-medications.html

[cxiv] Requests for proposals, supra note 140.

[cxv] Personal importation scheme. (2015, March 18). Australian Government Department of Health | Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). https://www.tga.gov.au/personal-importation-scheme

[cxvi] Mayr, M. (2017, September 19). International cooperation for inspections of API manufacturers. The place of the Certification Procedure in the global regulatory environment. Prague [PDF]. European Medicines Agency. https://www.edqm.eu/sites/default/files/20092017-m_mayr-international_cooperation_for_inspections_of_api_manufacturers.pdf

[cxvii] Ibid.

[cxviii] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, & Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. (2018). Q7 Good Manufacturing Practice Guidance for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients. Questions and Answers. Guidance for Industry. FDA.gov. https://www.fda.gov/media/112426/download