Imported Drugs Accounted for 57% of Overall Spending in Medicare

Which prescription drugs are most important to Americans in relation to the issues of drug importation, prices, safety – and even national security? This was a question we asked ourselves when thinking about the impact of our report, Not Made in the USA. So we looked at the top 100 drugs by expenditure in Medicare Part D, which are mostly, 85%, brand name drugs, many without generic availability in the U.S. Since we wanted to get a good idea of the percentage of drugs made abroad, this seemed like the perfect dataset.

We did not cherrypick these drugs. If 68% of the top 100 drugs in Medicare are foreign-made medicines, which is what our findings reveal, then it’s likely that a similar percentage applies to the entire U.S. brand name supply chain. That also goes for the 78% of active pharmaceutical ingredients in those drugs that are not made in the United States. This dataset includes many of the drugs that uninsured and underinsured Americans can’t afford locally, and therefore look to buy in Canada and other countries.

I spent a lot of time looking at the laws and regulations affecting country of origin information and claims on drug labels. You’ll find all of this published in the section called “Data and Methods,” which we’ve republished below. Dig in below, or download the entire report here.

Not Made in the USA - Data and Methods

The dataset of drugs for this report comes from the Medicare Part D Drug Spending Dashboard & Data.[1] The drugs chosen to determine their countries of origin were the top 100 drugs by total spending in 2018. Where there were generic drugs listed, we looked at the brand name product to assess the manufacturing origin of that drug.[i] Eighty-five of the 100 were single source drugs with no generic availability in 2018.

The principal method for determining the countries of origin was closely reading drug labels available in the U.S. National Library of Medicine.[2] Where those labels were ambiguous, researchers looked to the FDA Labeling-Package Insert drug information.[3] In several cases, drug manufacturers were contacted directly by phone or email, and answers were recorded to obtain the information. The manufacturing location data for each drug is broken down by both the locations of the FDF and API manufacture. For example, in the case of the drug Januvia (sitagliptin), the API is made in Italy and the FDF in the UK.

Data on drug prices came primarily from GoodRx.com and PharmacyChecker.com. The report compares retail drug prices available at U.S. and foreign pharmacies. Average U.S. retail prices came from GoodRx.com, and, in a few cases, Drugs.com. Average Canadian and other international pharmacy prices came from prices listed by PharmacyChecker-accredited online pharmacies on PharmacyChecker.com. The drugs for which prices were compared were those available for purchase internationally. Average Canadian pharmacy prices came from online pharmacies that only process international prescription orders from a licensed Canadian dispensing pharmacy. The average of other international pharmacy prices came from international online pharmacies that process prescription drug orders of medications approved for sale in the following countries: Australia, Canada, India, New Zealand, Turkey, and the United Kingdom.[ii]

2.1. Explanation of Dataset Focus on Brand Drugs

Concerns about the safety of the U.S. drug supply often center on generic drugs.[4] “The Geography of Prescription Pharmaceuticals Supplied to the U.S.: Levels, Trends and Implications,” published in the National Bureau for Economic Research in 2019, takes a deep dive into the FDA’s importation data, information generally shielded from the public, to shed light on the supply chain of generic drug products. A line from that report reveals the lack of data on brand name drugs:

“We do not have information on the manufacturing location of branded, non-generic drugs, nor on over-the-counter non-prescription formulations.”[5]

By focusing on brand name prescription drugs, this paper helps address that research gap. Understanding the supply chain and country origins of brand name drugs, in particular, is important for the following reasons, which are interrelated:

1) Their exorbitant prices in the U.S. relative to other countries

2) Their large share of all prescription drug expenditures by federal, state, and municipal payors

3) Their countries of origin are almost entirely U.S. allies and friendly trading partners

4) Misconceptions about drug importation, ones that have likely prevented regulatory reforms allowing importation that would help Americans and taxpayers spend less on prescription drugs

Identifying the countries of manufacture of brand name drugs, in addition to those of generic drugs, is highly relevant to current policy developments pertaining to drug prices and importation. Generic drugs make up about 90% of all prescriptions dispensed in the U.S. each year.[6] Yet brand name drugs account for about 80% of all expenditures.[7] An April 2021 Kaiser Family Foundation analysis found that Medicare’s top-selling 250 drugs with one manufacturer (i.e., almost entirely brand name drugs) and no generic or biosimilar competitors accounted for 60% of net total Part D spending in 2019.[8]

According to research conducted by the U.S. House Ways and Means Committee published in 2019, drug prices at the wholesale level are about 75% lower on average in other high-income countries on 79 drugs that make up 60% of spending in Medicare Part D.[9] That dataset consists only of brand name drugs. For decades, federal law, with limited exceptions, has protected the pharmaceutical industry from price competition from the foreign, wholesale drug prices by prohibiting all commercial entities except for the manufacturer from importing those same drugs at lower prices.

2.2. Federal Law and Drug Labeling: Differing Definitions of an Imported Drug

We reviewed the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), the Tariff Act, and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Act because they each can affect how a drug manufacturer labels a drug product in terms of its country of origin. The interplay of the various requirements can prove difficult for consumers and policymakers to readily ascertain where a drug was made.

The FDA, which is responsible for enforcing the FDCA, and U.S. Customs and Border Protection, an agency with the Department of Homeland Security, play prominent roles in the importation of prescription drugs[10]:

- The FDA regulates which drugs can be imported.

- CBP, along with the FDA, regulates the physical importation of drugs.

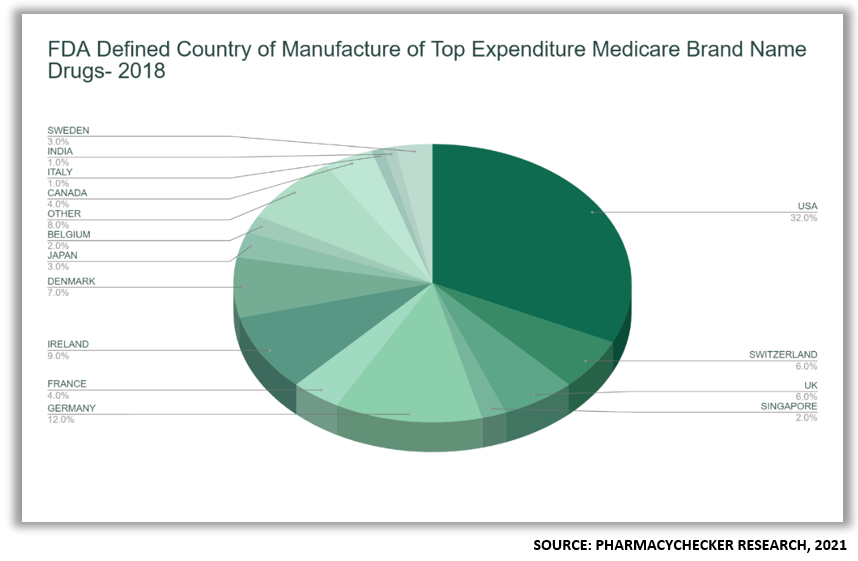

The FDA and CBP have different definitions for assigning a country of origin to a drug. To the FDA, the country where the final formulation of a drug occurs, including where it’s packaged, is the drug’s country of manufacture.[11] The FDCA does not require manufacturers to publish the countries of manufacture on prescription drug labels or otherwise make the information public.[12]

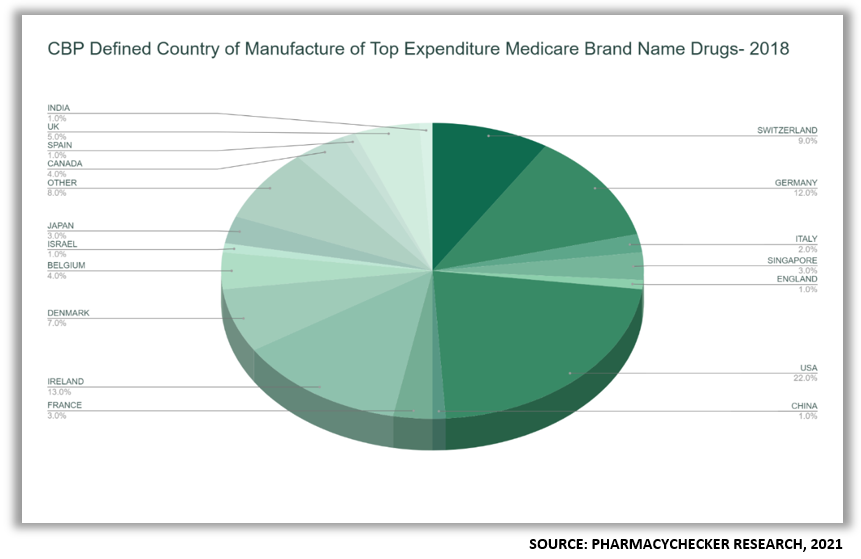

To CBP, the country in which the API is made is the country of origin.[13] Therefore, to the CBP, under most circumstances, an imported drug is one where the API was manufactured outside the United States.[14] There are exceptions to CBP’s definition: if a drug is substantially transformed during the manufacturing process regardless of where the ingredients came from, and/or when two APIs are combined into one drug formulation.[15]

Consider the drug Eliquis (apixaban). According to its label, the API of Eliquis, apixaban, is made in Switzerland, but it becomes an FDF in the United States. To the FDA, Eliquis is manufactured in the United States. To the CBP, Eliquis is an imported drug.

While the FDCA does not require drug companies to publish the countries of manufacture on prescription drug labels, the Tariff Act and the FTC Act add requirements and constraints on drug labels of imported products. [16] [17]

- The Tariff Act mandates that the country of a product’s origin is printed on the labels of all imported products and is enforced by CBP.[18]

- The FTC Act prohibits false or misleading “Made in America” claims.[19]

In understanding the requirements of the FDCA, the Tariff Act, and the FTC Act, and how they work together, with access to the manufacturer’s label, it usually becomes clear where a drug was made, both the FDF and the API.

2.2.1. The Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

The FDCA governs prescription drug licensure, which includes labeling. The law requires only that a manufacturer’s drug label bear the name of the manufacturer and any address associated with the company. The address does not have to be where the drug was made. For instance, the location and country identified on the label can be a manufacturer’s principal place of business, such as corporate headquarters, instead of the country of the factory where the drug was made. While the FDCA does not require country of origin labeling, its section on misbranding requires truthfulness in labeling, which applies to labels on imported drugs. Under the FDCA, a drug is considered “misbranded" if “its labeling is false or misleading in any particular.”[20] When a drug company labels a product in violation of the Tariff Act, it may run afoul of the misbranding regulations.[21]

2.2.2. The Tariff Act of 1930

The Tariff Act of 1930 as amended requires imported products to be labeled with the country of manufacture.[22] If an imported product mentions a country on its label that is not the country of manufacture, then it must clearly add information showing the name of the country of origin. The Tariff Act is enforced by the CBP pursuant to the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 19 134.46:

“Section 134.46, Customs Regulations (19 CFR 134.46) provides that in any case in which the words ‘United States’ or ‘American,’ the letters ‘U.S.A.,’ any variation of such words or letters, or the name of any city or locality in the United States, or the name of any foreign country or locality other than the country or locality in which the article was manufactured or produced, appear on an imported article or its container (emphasis added), there shall appear, legibly and permanently, in close proximity to such words, letters or name, and in at least a comparable size, the name of the country of origin preceded by ‘Made in...’”[23]

In addition to the phrase “made in,” if the country is preceded by the phrases “Product of,” or “Manufactured by,” that is the country of origin, according to CBP personnel in an email exchange with PharmacyChecker (P.J. Ghazi, personal communication, July 21, 2020). A drug manufacturer cannot list a U.S. address alone without including the country of manufacture for a drug with a foreign made API. Thus, a drug labeled solely with a U.S. address, without any marking of a foreign location, would be considered, by the FDA and the CBP, to be manufactured domestically.

Here is how this relates to our data:

- 22 of the 100 (22%) drug labels examined listed only a U.S. address.

- For those 22 drugs, we called the marketing drug companies to confirm their countries of manufacture.

In that respect, under CBP’s definition, 78% of the drugs examined in this research were foreign made.

2.2.3. The Federal Trade Commission Act

The Federal Trade Commission Act makes it illegal to market a product with the phrase “Made in the U.S.A.,” unless “all or virtually all” the contents of the product are domestically manufactured.[24] The FTC Act’s bar is very high for a company to make this claim, and this may affect the decisions of drug manufacturers not to use it.

Even though 22 drugs in the dataset were identified as manufactured domestically, both API and FDF, only two drug labels included the words “Made in the U.S.A.” It is conceivable that a drug with a domestically manufactured API, one labeled only with a U.S. address, cannot make the claim “Made in the U.S.A.'' if any of its excipients (i.e., inactive pharmaceutical ingredients) are imported.

Across many consumer goods, affixing “Made in the U.S.A.” is commonly considered a worthwhile marketing claim.[25] In the case of a patented, brand name prescription drug for which there is no alternative, the “Made in the U.S.A.” claim may not play the same role for the patient consumer. In the prescription drug market, there is far less consumer choice than in most other markets. When patients fill prescriptions at a pharmacy, they often do not have a preference or even the option of the manufacturer beyond brand vs. generic. Additionally, insurers and pharmacy benefit managers often make it difficult for patients to access a branded drug when a generic alternative is available, by requiring prior authorization, a process through which a prescriber must obtain special approval from an insurer if a brand is requested instead of an available generic.[26] In some cases, due to concerns about low quality generic or narrow therapeutic index drugs, where a generic drug from a specific manufacturer is not working for a patient, that patient or their provider may ask the pharmacy for a manufacturer-specific drug, whether it is a brand or generic.[27]

2.3. Countries of Origin of Top 100 Medicare Part D Drugs by Expenditure in 2018

In 2018, 68% of finished drug products and 78% of active pharmaceutical ingredients of the top 100 Medicare prescription drugs by total expenditures sold in the United States were imported. Those imported drugs accounted for 57% of overall spending in Medicare.

- Under CBP’s definition, 78% of the 100 drugs examined were foreign made because the API was made outside the U.S., without regard to where the finished product was made.

- Under FDA’s definition, 68% of the 100 drugs examined were foreign made because the finished drug was imported.

- 98% of the drugs assessed were made in countries that have comparable if not better systems of pharmaceutical regulations to the U.S. according the CBP.

The Exceptions:

- Neurontin (gabapentin). The label reads that it is “Made in India,” indicating that both the API and FDF are manufactured in India. Gabapentin is widely available in the U.S. as a generic.

- Imbruvica (ibrutinib). The label reads “Active ingredient made in China.” A drug company representative said that “the manufacturing, testing, packaging [of Imbruvica] is done across multiple locations in the USA. This indicates that the API is manufactured in China and the FDF, in the USA

- Apart from Imbruvica, all countries of origin making brand name drugs from the dataset are democratic allies, indicating that national security vulnerability is less of an issue when it comes to brand name drugs.

2.4. 2021 U.S. vs. International Retail Brand Name Drug Prices

In addition to country of origin, “Not Made in the USA” researchers collected and compared U.S. and foreign retail drug prices of products in our dataset. We compared our data to the robust analysis into comparative international drug pricing from the Rand Corporation’s 2021 report called “International Prescription Drug Price Comparisons: Current Empirical Estimates and Comparisons with Previous Studies.”[28] Its focus was on wholesale prices. The data in “Not Made in the USA” on retail drug prices corresponded strongly with Rand’s analysis.

Rand’s top-level finding on brand name drug prices is that U.S. prices are 344% higher than the average of member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation Development (OECD). Reversing the percentage into a discount, Rand found that prices are on average 71% lower outside the United States. For the top 60 drugs by sales in Rand’s study, the difference is 394% higher in the U.S., meaning approximately 75% lower outside the United States. The respective finding in “Not Made in the USA” is 75.53%. For just pharmacies in Canada, Rand’s findings show prices are 294% higher in the U.S., meaning 66% lower in Canada. The respective finding in “Not Made in the USA” is 70.18%.

The parallel findings, especially in view of the different methodologies, between the Rand report and this report on pricing, point to the accuracy of the data.

The price comparisons in Appendix A were collected in May 2021. The dataset for pricing is based on the top 100 brand name drugs by expenditure in Medicare in 2018 that are available for sale from foreign online pharmacies that ship medication internationally.[iii]

- Top brand name drugs sold in U.S. pharmacies are 385% more expensive than international mail-order drugs.

- Top brand name drugs sold in U.S. pharmacies are 357% more expensive than available at Canadian mail-order drugs.

[i] Spending on those generic products is captured in the source data.

[ii] PharmacyChecker-accredited international online pharmacies process orders for non-controlled prescription drugs for patients with a valid prescription and filled by pharmacies licensed in the countries where they operate. The PharmacyChecker Verification Program online pharmacy safety standards are available at: https://cdn.pharmacychecker.com/pdf/VP+Accreditation+Standards+and+Guide.pdf.

[iii] Drug prices came from foreign online pharmacies that are PharmacyChecker-accredited, meaning online pharmacies that meet important safety criteria. Prices are taken from pharmacies that dispense drugs approved in Australia, Canada, India, Israel, New Zealand, Turkey, or the United Kingdom. Canadian pharmacy prices are those taken from pharmacies that only dispense medication in Canada.

[1] Medicare part D drug spending dashboard. (2020, December 22). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services | CMS. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Information-on-Prescription-Drugs/MedicarePartD

[2] The DailyMed database. (n.d.). DailyMed. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/

[3] FDA-Approved Drug Database. (n.d.). Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/

[4] Kaygisiz, N. B., Shivdasani, Y., Conti, R. M., & Berndt, E. R. (2019, December). The geography of prescription pharmaceuticals supplied to the U.S.: levels, trends and implications. National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w26524

[5] Ibid.

[6] Generic drugs. (2021, February 5). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/buying-using-medicine-safely/generic-drugs

[7] Mikulic, M. (2021, September 20). U.S. brand and generic prescription drug spending 2005-2020. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/205036/proportion-of-brand-to-generic-prescription-sales/

[8] Lee, C. (2021, April 19). Analysis finds that a relatively small number of drugs account for the majority of Medicare prescription drug spending. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/medicare/press-release/analysis-finds-that-a-relatively-small-number-of-drugs-account-for-the-majority-of-medicare-prescription-drug-spending/

[9] Ways and means committee releases report on international drug pricing. (2019, September 23). Ways and Means Committee. https://waysandmeans.house.gov/media-center/press-releases/ways-and-means-committee-releases-report-international-drug-pricing

[10] Import basics. (2020, February 27). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/industry/import-program-food-and-drug-administration-fda/import-basics

[11] Customs and FDA at odds on pharmaceutical labeling. (2016, September 15). Benjamin L. England & Associates. https://benjaminlengland.com/customs-fda-odds-pharmaceutical-labeling/

[12] Federal food, drug, and cosmetic act (FD&C act) (Title 21). (2018, March 29). United States Code. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/laws-enforced-fda/federal-food-drug-and-cosmetic-act-fdc-act

[13] Trade agreements Act of 1979, 19 U.S. code § 2518 – Definitions (1979). https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title19/chapter13&edition=prelim

[14] Customs, supra note 23.

[15] Import Basics, supra note 22.

[16] Tariff act of 1930, 19 U.S. code §2571 —Customs duties (1930). https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?path=/prelim@title19/chapter4&edition=prelim

[17] Federal Trade Commission Act. (2018, December 14). Federal Trade Commission. https://www.ftc.gov/enforcement/statutes/federal-trade-commission-act

[18] Tariff act of 1930, supra note 28.

[19] Federal Trade Commission Act, supra note 29.

[20] Misbranded drugs and devices, 21 U.S. code § 352: (1966). https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=(title:21%20section:352%20edition:prelim

[21] Orenstein, J., & Campos, L. (2014). Origin of the pieces: how to determine a pharmaceutical product’s “country of origin.” Public Contract Law Journal, 43(3), 489–506. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44740643

[22] Marking of imported articles and containers, 19 U.S. code § 1304 (2020). https://uscode.house.gov/view.xhtml?req=(title:19%20section:1304%20edition:prelim

[23] Code of federal regulations (CFR) 19 134.46: (1997, August 20). Electronic Code of Federal Regulations. https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-19/chapter-I/part-134

[24] Federal Trade, supra note 29.

[25] Regole, R. (2015, November 25). The power of manufacturers using 'Made in the USA' in marketing. IndustryWeek. https://www.industryweek.com/leadership/article/21966360/the-power-of-manufacturers-using-made-in-the-usa-in-marketing

[26] Barnett, B. (2021, January 1). Under prior authorization, who is choosing Americans' medicines? STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2021/01/01/prior-authorization-whos-choosing-americans-medications-doctors-or-insurers/

[27] Ibid.

[28] Mulcahy, A.W., Whaley, C.M., Gizaw, M., Schwam, D., Edenfield, N., & Becerra-Ornelas, A.U. (2021). International prescription drug price comparisons: current empirical estimates and comparisons with previous studies. RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2956.html